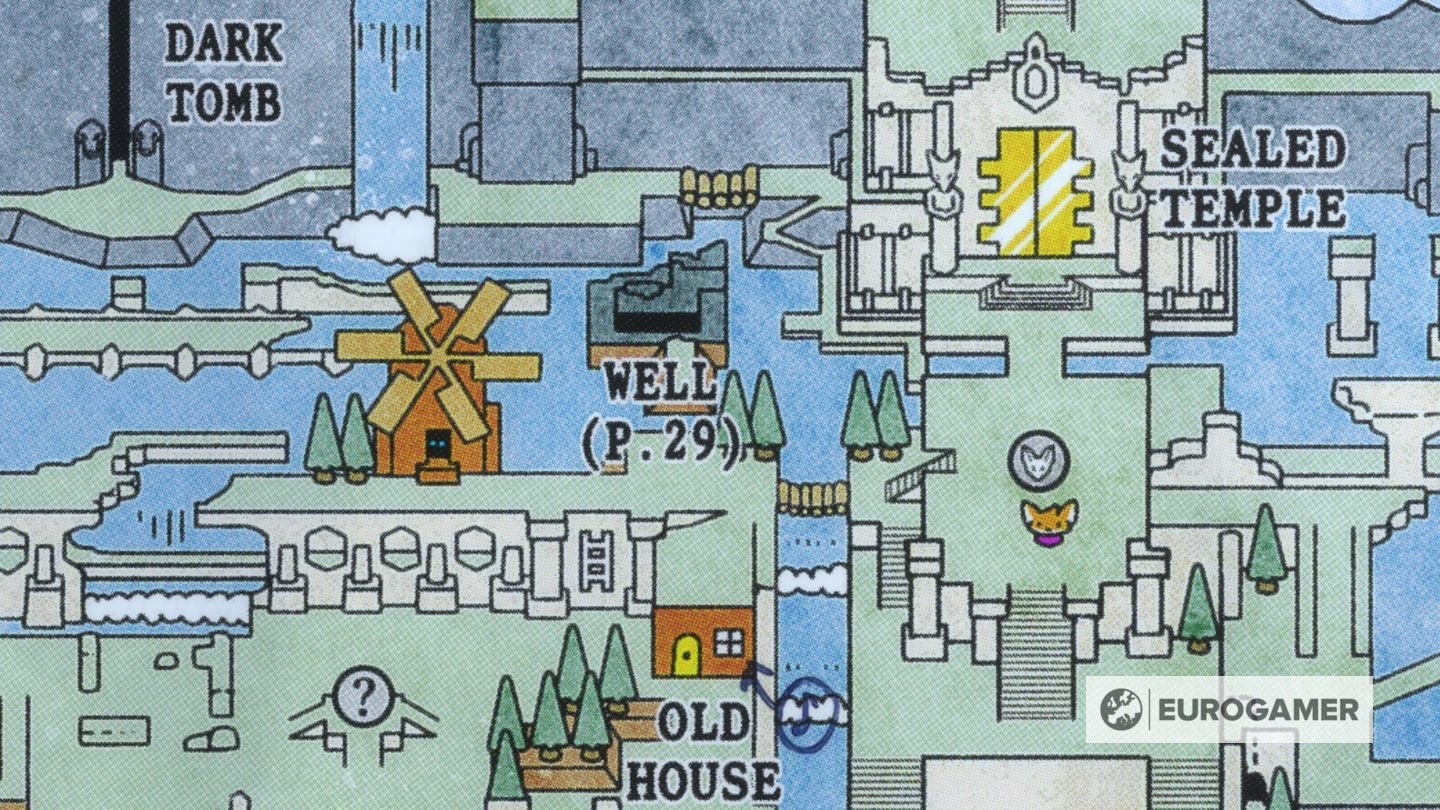

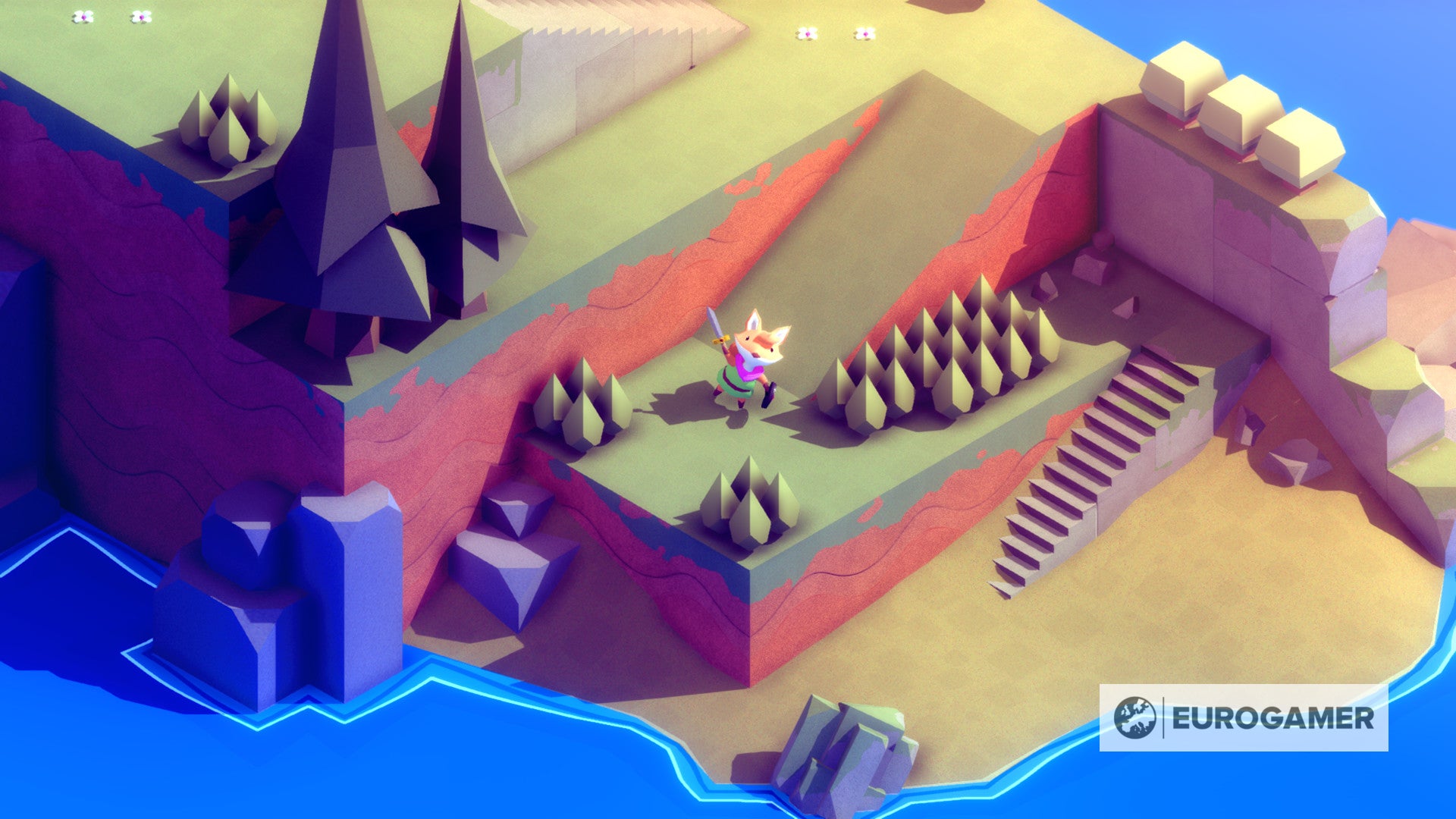

These are my favourite worlds. The best worlds, if you ask me. The best of all possible worlds. Not open worlds, not free-roaming, certainly not endless or procedural worlds. Instead these worlds are a bounded place, a place as boldly self-contained - as compact and weather-tested - as a bird’s nest in the high branches of an old tree. And as intricate too: woven together, each piece locked in position by dozens of other pieces. Maybe scavenged, maybe stolen, a thing reflecting a thousand other mini-things that came together to make it. How do birds even know when a nest is complete? For a world like this, a world in a videogame, rather than up high in an old tree, completeness shows up in the details. It will be a single detail that sticks in the mind and makes you think: Cor! Look at that. Maybe I should be taking notes here. A single detail. It’s not something big. Generally, it’s something small. Something hidden. Tucked away, say, under a bridge? Yes! Under the bridge, a campfire. Just say the words and I am back there. Late on in A Link to the Past, which is still arguably the best Zelda game, and certainly the most committed in its Zeldaishness, I realised that there was a gap in the map: a bridge, which may have had something under it. I found a path eventually, and under the bridge was a sleeping fellow lying by a campfire. Rustic domesticity. A pocket of cosiness in an increasingly frightening world. This fellow gave me a bottle, which in a Zelda game is always a useful thing to have one more of. But more than that, just by being there, in this secret piece of the map that I had to first imagine might exist in order to actually locate, he gave me something much more. He gave me a glimpse into the minds of the designers - of the way their minds worked when they came together, certainly. And an invitation, perhaps - encouragement to allow my mind to work in the same way. A Link to the Past is just one of a handful of games that Tunic reminds me of. I had almost written it off as a secondary text, to be honest: that top-downish topiary world, the cinnamon roll trees of Hyrule swapped out for fat little darts, the boyish hero in green replaced with a plucky fox. But this isn’t a clone or a copy or an idiotic riff on cherished memories. It’s proper synthesis. Tunic takes lessons from A Link to the Past - about how to build a world and layer its puzzles until they become a kind of strata of secrets and possibilities. Just as it takes lessons from Souls games, both lessons you learn juddering through your shield arm as you block and then time a strike in the Soulsy combat, and lessons you learn in that moment of gleaming recognition as you kick a ladder down from its mount on a wall and realise that a long journey through unknown lands has lead you back here. Back to a place you already knew very well - or thought you knew, at least. Zelda and Souls combined - not merely the iconography or the main beats. Rather, Tunic is the understanding gained by playing both and really thinking about why they are the way they are - how they create, as a magician might put it, their particular effects. Zelda and Souls and those few other games - to name them would be a spoiler - are used almost as writing prompts, as a creative shove into new territory. This is a game that borrows, then, but it reworks what it borrows. It’s Conan Doyle filtered through Ellen Raskin: inspiration internalised and transformed. Alchemy I guess. Oh, to put it another way: the success of Zelda means it got codified. You’d approach each new game asking: what’s the overworld this time? When do I get the boomerang? Breath of the Wild is one response to that problem. Maybe Dark Souls was in part a response to that too, actually. This game is another response. Tunic! So you are a fox let loose in a bright, clean-edged world. Rock and grass and earth! You explore dappled forests and wasted shores, and you gather a sword and shield. You take on monsters and pick your way through ruins and slowly start to unravel an ancient mystery, one boss at a time. At this level, Tunic is already a very good time, I think. The world switches from Spring fields to ruined town - of course there is a windmill, of course there are telescopes - to cisterns pooling with green water and temples where something metallic and alien glints in the walls. You view the world at an angle, and the designers of this place are not above using that angle to create blind spots where they might put something exciting - a chest or, even better, a concealed tunnel. They are teaching you to sound out the world through imagination as well as the things that are immediately obvious. (At one point, to make this point even clearer, they straight-up turn the lights out.) Enemies are great. Slimes and spiny things made of glittering shards of cold death. Skudding laser-equipped drones made of old rock. Hippo-alikes with swords and shields and prog capes to finish the look. One level is entirely frogs, all of them attending a kind of academy for frogs. Each enemy is capable of doing you in by themselves if you just rush in. Instead, use the trigger targeting but do not over-rely on it - be wary of the way it bonds you to just one foe when you’re often surrounded by many. Hold your shield out, but do not let it slow you down. Dodge roll but do not let it eat through all your stamina. Use magic items but do not forget that mana does not recharge on its own here. Stamina and mana? Even here, Tunic takes the best of Souls and Zelda. You can extend your health bar by finding and cashing in certain items - you can extend all your stats this way - but for health you can also collect more estus-flask-equivalents, which initially come in several pieces that must be put together, like Zelda’s hearts. The systems from two games are reworked, the secret harmonies found until you can’t see the joins. The same goes for bosses - are they Zelda bosses or Souls bosses? At times they are both, and ultimately I came to understand that they are neither - they are Tunic bosses, terrifying, tactical, brisk puzzles that encourage you to respec your character on the fly, picking through items like bombs that you may have collected, through new weapons like magic staffs or…hmm, I feel like I should spoil no more here. Not even the mid-game treat that turns you into a cross between Batman and Mr Tickle. This is a good game - explore, defeat baddies and bosses, level up, open up the world a bit and sound out new dungeons, working your way, you tell yourself, towards the final boss, the moment where the world is in the balance and all that jazz. But it is also half the game. It is half of what Tunic is. Maybe less than half, in terms of the sheer amount of time you will spend thinking about it, turning it over. “There is another world,” as the quote goes - it’s maddening trying to track down who actually said it originally - “but it is in this one.” To access the other half - the other game nested inside of Tunic, if you will - you have to step back a bit. Step back from the fox, the sword and shield, the enemies and the headlong rush of adventure. Consider the world in its totality, its ragged edges, where distant points might have unusual similarities. Think about the things you pass on your journey that you do not yet understand. What might they mean? What might they do? Two things help Tunic’s brilliant hidden game to truly live, and one of them I really do not want to spoil for you, because when I first properly understood it, I realised that Tunic was showing me something I had genuinely never seen a game do before. But the other thing that helps? Tunic’s deeper layers, the weird, menacing puzzley permafrost, work so well because at first these layers obey the rules of the more exposed layers. They require the same kind of thinking - just extended, to the point where you might feel you’re going a bit too far. Which is to say: in Zelda games - in Souls games - you are used to getting items that make you see new possibilities in the landscape and in your place within it. You are used to coming across features which, for the time being, do not seem to make much sense, because you lack the correct lens to view them through - for now. So Tunic’s ranginess, its beautiful oddness, is harmonious, because the way you approach thinking about it is ultimately the same way you tease out how items work here - understanding items took me an age - and how levelling works, and how fast travel works, and, and… How deep do you want to go? In truth, the very landscape of Tunic speaks of the precision and artificiality of design: all those clean lines and echoing, repeated angles forming a world that adds up to a sort of hymn to graph paper and a freshly sharpened pencil. I’m tempted to say you could enjoy the more immediate aspects of Tunic without giving too much thought to this stuff. But then, really? Tunic’s best puzzles are designed for collaboration and forums and the sharing of notebooks and screenshots, yes, but they’re also designed to sit in your unconscious and tick away to themselves quietly, and then one day you find yourself staring at something strange on the screen and you suddenly realise you know exactly what you have to do with it. Taken as a whole it reminds me, in a way, of that feeling I get sometimes when I’m on holiday, jet-lagged in a once-distant country, and I go to a supermarket - for Paracetamol or something. I don’t speak the language. I don’t understand a lot of the customs. A lot of the products seem semi-familar, though. Semi-familiar enough to suggest their own potential uses, while, crucially, allowing for surprises. It’s exciting, tantalising. The supermarket! Everything looks great. And quietly unusual. Is that fruit or some kind of loofah? Should I chew these or swallow them to cure hiccups? Where shall I push my cart next? I reckon that the success of a game like Tunic, in particular - one that follows in the footsteps of games like Zelda and Dark Souls - hinges on the correct deployment of what I shall briefly have to call the pleasures of Distant Supermarket Thinking. In the best of these games, filled with action and adventure and wholesome excitement, we are perpetually wide-eyed, perpetually alert for delights that we know we cannot anticipate. Old ideas delivered in unfamiliar ways; things that seem familiar but are not what they initially appear to be. In bad or even middling Zelda-alikes, you get craft and not much else. In the best, you get imagination, and you get dazzle, you get taken somewhere new, in the midst of all this stuff that feels so chummy and time-worn. The difference probably comes down to a lot of things: time, passion, having a clear idea of what you want to achieve, even if it’s wildly complex and ambitious. And more: a certain sympathy with the form. In this regard, here’s another mangled quote: they say that only a bad poet hates the rules. This is because a good poet thrives with restrictions, with established expectations that can be twisted, subverted, inverted. They find limitations and traditions propulsive, accelerative. This is Tunic to its core. Consider the fox. You are not a fox by accident in this game, I think. One of my first thoughts about Tunic, right back at the start, is that your wibbling fox hero didn’t actually seem very foxlike. Too much bounce. Too much cheer. Too much innocence. They did not match the gorgeous midnight creatures I sometimes glimpse freeze-framed by a blast of security light at the end of a driveway in the rare hours. Haunted face, blazing eyes, one foot raised and paused mid-step. These are tricksy animals. This is projection, I know, but foxes always feel like deep thinkers, privy to wild and complex thoughts. They do not always bounce cheerfully through this world. And then, over time, I understood. Your hero in Tunic is not yet a fox. They are a cub. And so you, the player, must become the fox for them.