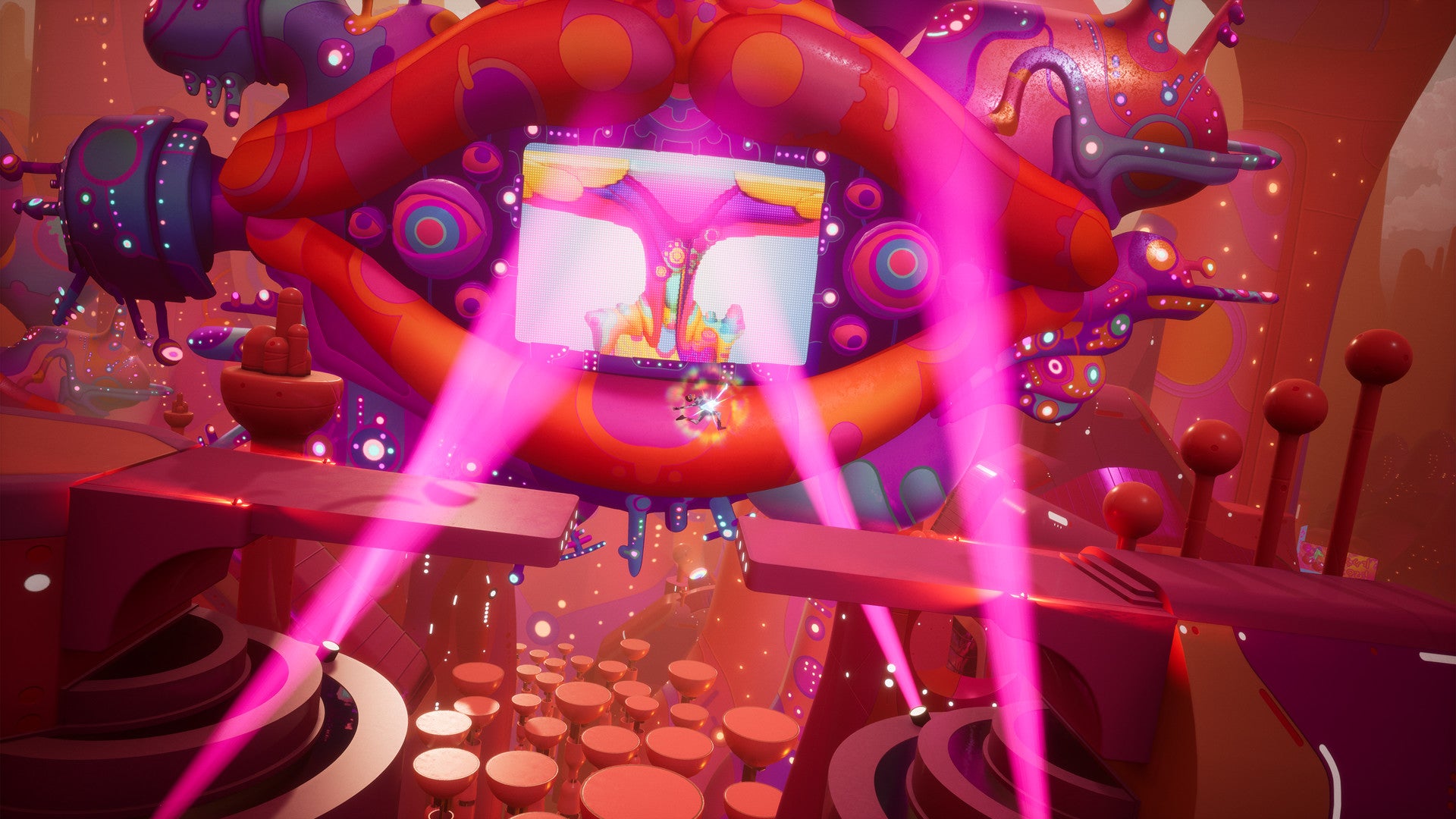

We’ve gone back to a few real gems, so for more catch-up reviews like this one head to the Games That Got Away hub, where all our pieces from the series will be rounded up in one convenient place. Enjoy! The trick to understanding what the The Artful Escape is trying to do, I reckon, is to embrace the fact that this music game doesn’t actually have any particularly memorable music in it. For me at least. It’s certainly lovely to listen to while you’re playing, and the big moments rise to their epiphanies and then die away with great poise, but once the game was switched off nothing really lingered in my mind. I couldn’t hum a leitmotif or whatever they’re called. I couldn’t recall a favourite burst of guitar. This is the thing, though: it doesn’t matter. The soundtrack here is a sort of grand, proggy bed of pleasant noise for the solo noodling you do over the top of everything. The whole game is a solo that’s got out of hand. And that’s the trick, the key to the whole thing, I suspect. The Artful Escape doesn’t want to teach you music and doesn’t really want you to play music. It wants to make you feel the way you imagine people feel when they’re playing music for a huge crowd with everything cranked to eleven. Do you think Ziggy, or David St Hubbins, could hear much of what was going on when the crowd was screaming and the earth was shaking? They were lost inside the sensation somewhere. They were freaking out on a moonage daydream. This is a lovely game, anyway. You play a young fellow who’s related to a local folk music hero and expected to keep playing those songs about coal miners and ghosts of electricity that howl in the bones of a person’s face. But he doesn’t want to be Dylan. Maybe what he wants to be is Ziggy - a catsuited glam rocker banging on about nebulae over screaming cheeseball riffs. What follows from this slow realisation is a journey through prog and glam album covers, from the small town where he lives in shadow, out into space with whales and giant turtles and Blade Runner flying cars, and back in the end to play a show - and to show everyone who he really is. At first, the sheer density of The Artful Escape can be overwhelming. This is an Annapurna joint, so there’s Hollywood stars doing the voices (Carl Weathers is absolutely sensational - he really does have a stew going), and the town where it all kicks off is a sort of teetering Bruegelian Babel, albeit one with coffee shops that have punning names and a rattly funicular to take you from one street to the next. The game works on a 2D plane, and it has that kind of loose-limbed, cardboard cut-up feel you get from Gilliam animations. It’s absolutely full of stuff: jokes, references, toy robots and old record players. At night the shops in town have a sort of wine-bottle thickness to the glass. Brass twinkles on fixtures and dandies flap around worrying about dandyish things. It’s almost too much, and almost too clever. The danger is that at any second we might pass through some event horizon of clustered penny-farthings and hit the Custardo Singularity. Spaghettification all round! This never happens, because soon you’re off on your adventure, cruising the lurid iconography of seventies rock. The game is very simple: it’s a 2D platformer with a double-jump and a sort of float move. You slide down slopes and clamber up ridges and avoid dropping yourself into the abyss. But while you do all this you hammer the X button and play your guitar - a wailing solo that pretty much rushes out of you like silly string. All the notes you could ever want, but just press X and hold! And when you play the guitar wonderful things happen. Back in town your solo brings all the street lamps to life - a properly memorable videogame moment. When you cross pink mountains it ricochets off the snow and ice. In vividly coloured woods it brings flowers to full bloom and sends fireflies buzzing. Run and jump and double-jump, sure, but look at everything else that’s happening because of you. The game pings between long, generous platforming runs through wild locations, and a series of hubs where you can wander back and forth and chat to people and be groovy. The visual inventiveness is almost gratuitous: one minute a level is Heironymus Bosch, and the next it’s more migraine-during-a-team-lunch-at-the-Rainforest-Cafe. Everything has had thought put into it: is it me or do the elevators in a hub buzz with that particular chunky electrical hum you get when you plug a guitar into an amp? There’s a joy to the endless quick changes, to the glittering bits of business that zip past before you can properly clock them. It’s a game that calls out for the second playthrough, and what I particularly love are the hints of showbiz artifice that has always been a part of rock - the rickety movement of huge beasts, as if they’re running on old machinery, the neon black-light paint splattered on the surfaces of hot Jupiters. Cue the druids and their tiny Stone ‘Enge. What else? Bosses, of a kind, all very generous: you match their button presses not to match their notes but accompany, harmonise, and ultimately overwhelm them. You travel from space to huge ancient temples, hopping lanterns and Japanese fish. It’s not a truly great platformer - most of the time it’s absolutely fine, but when things get busy, the air can be thick and turning slow, and at its very worst it feels like you’re moving a marionette operator around and they’re in turn operating the marionette. But it doesn’t matter - platforming here is a bit like playing the guitar. Press the appropriate button and believe. Ultimately you’re watching a performance as much as giving one, and for a game this sly and playful, I can live with that. This is a rush, a conceit, a virtuoso doodle. It’s a gas. It’s a lark.