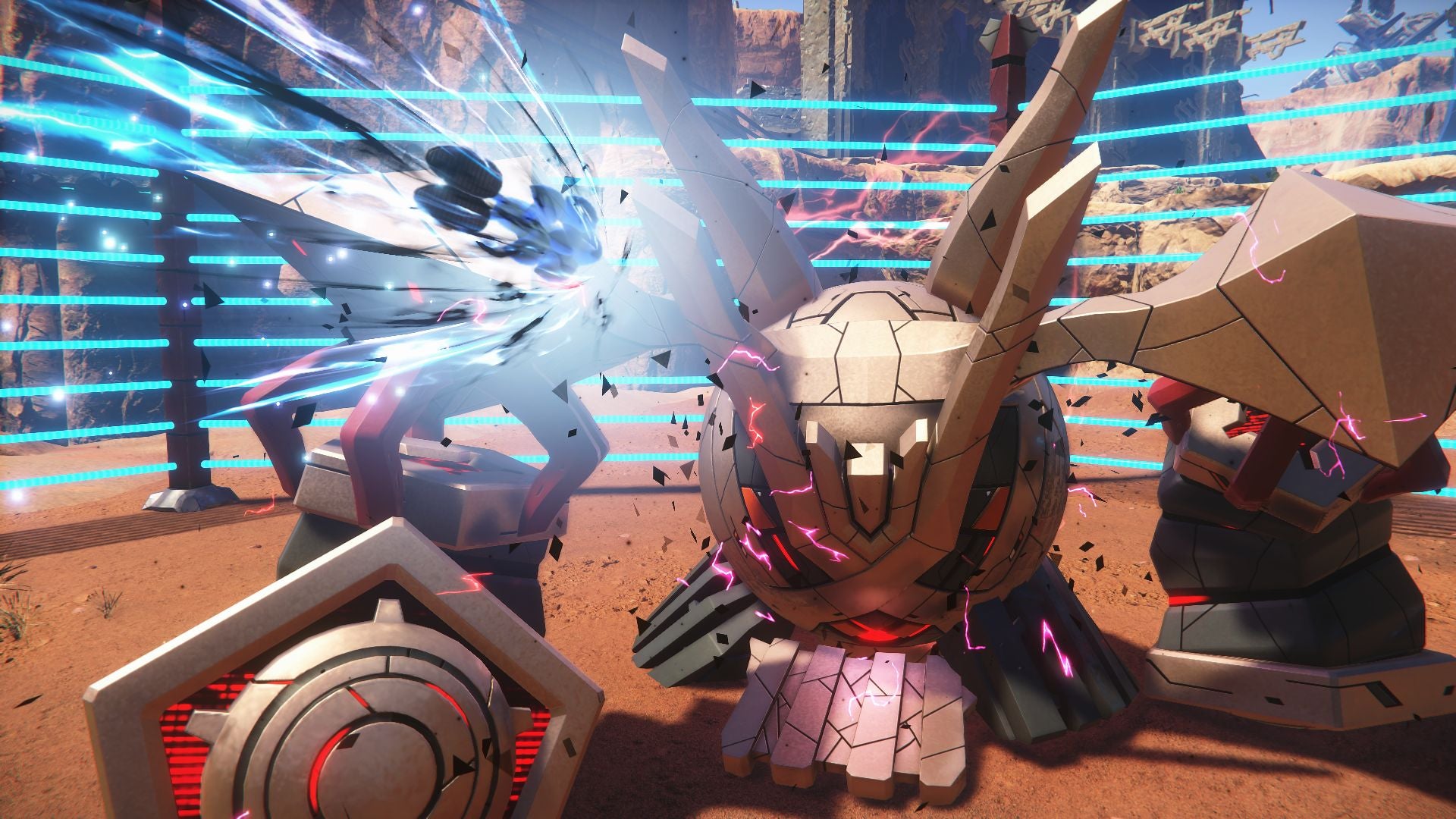

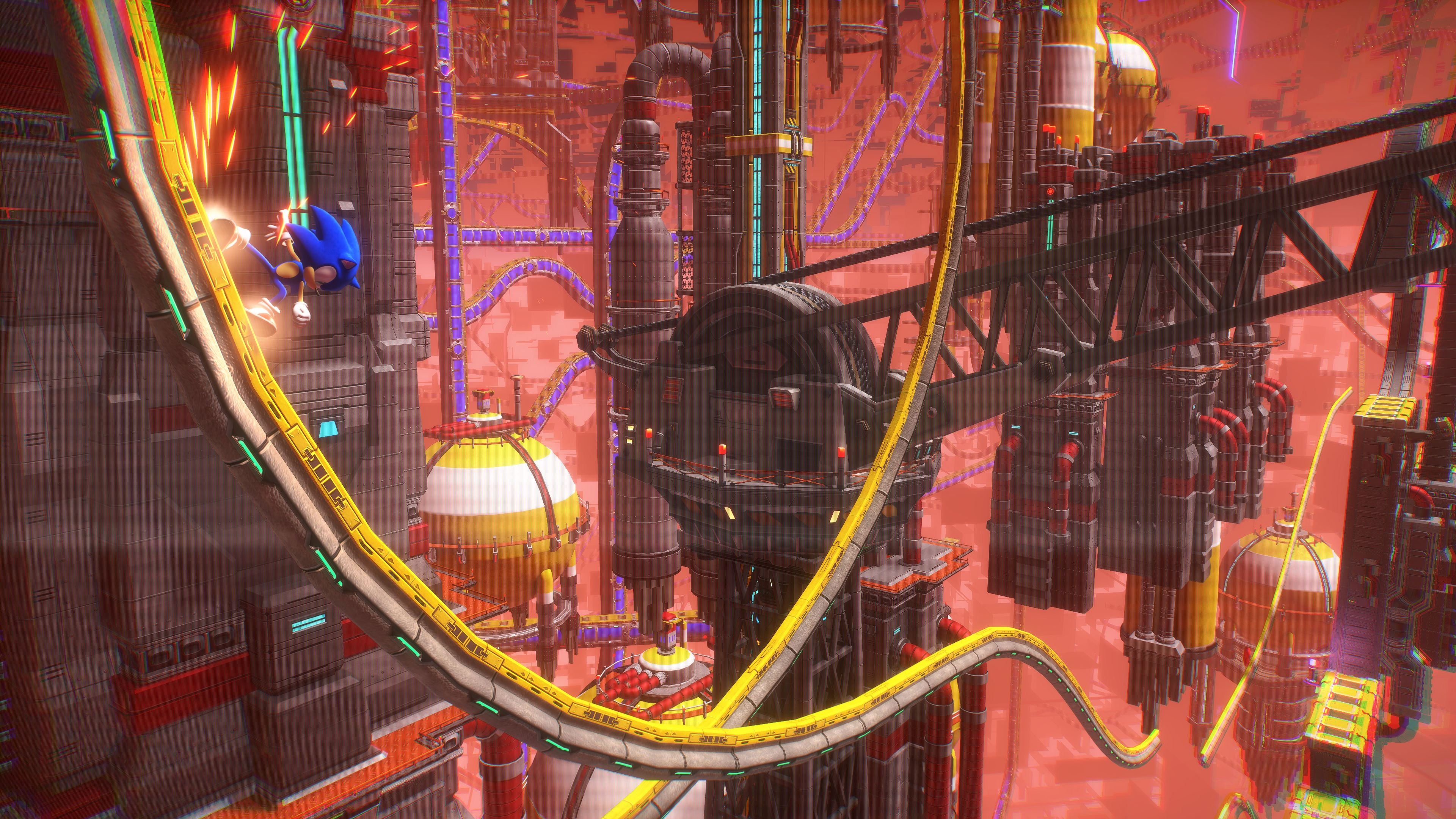

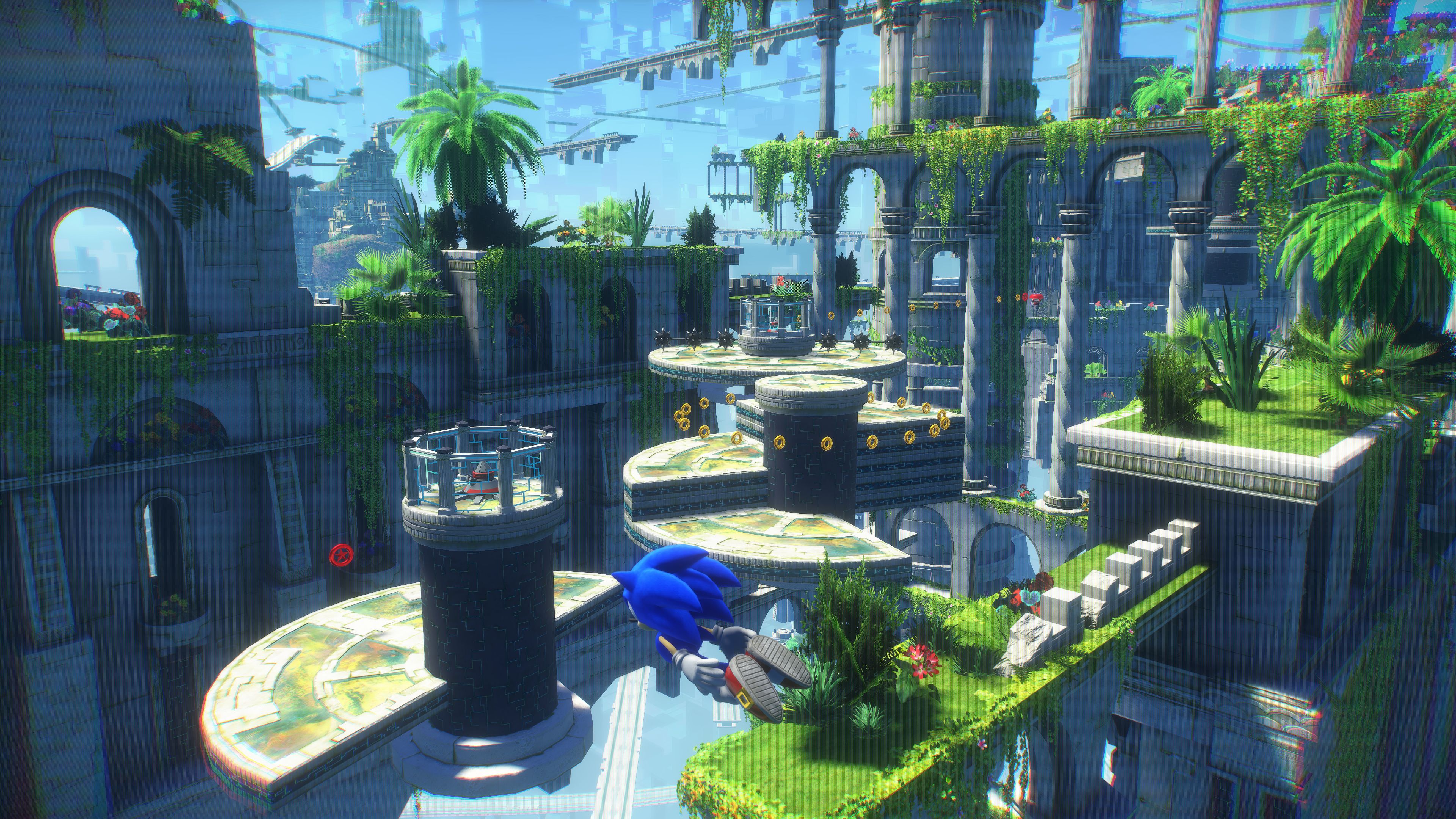

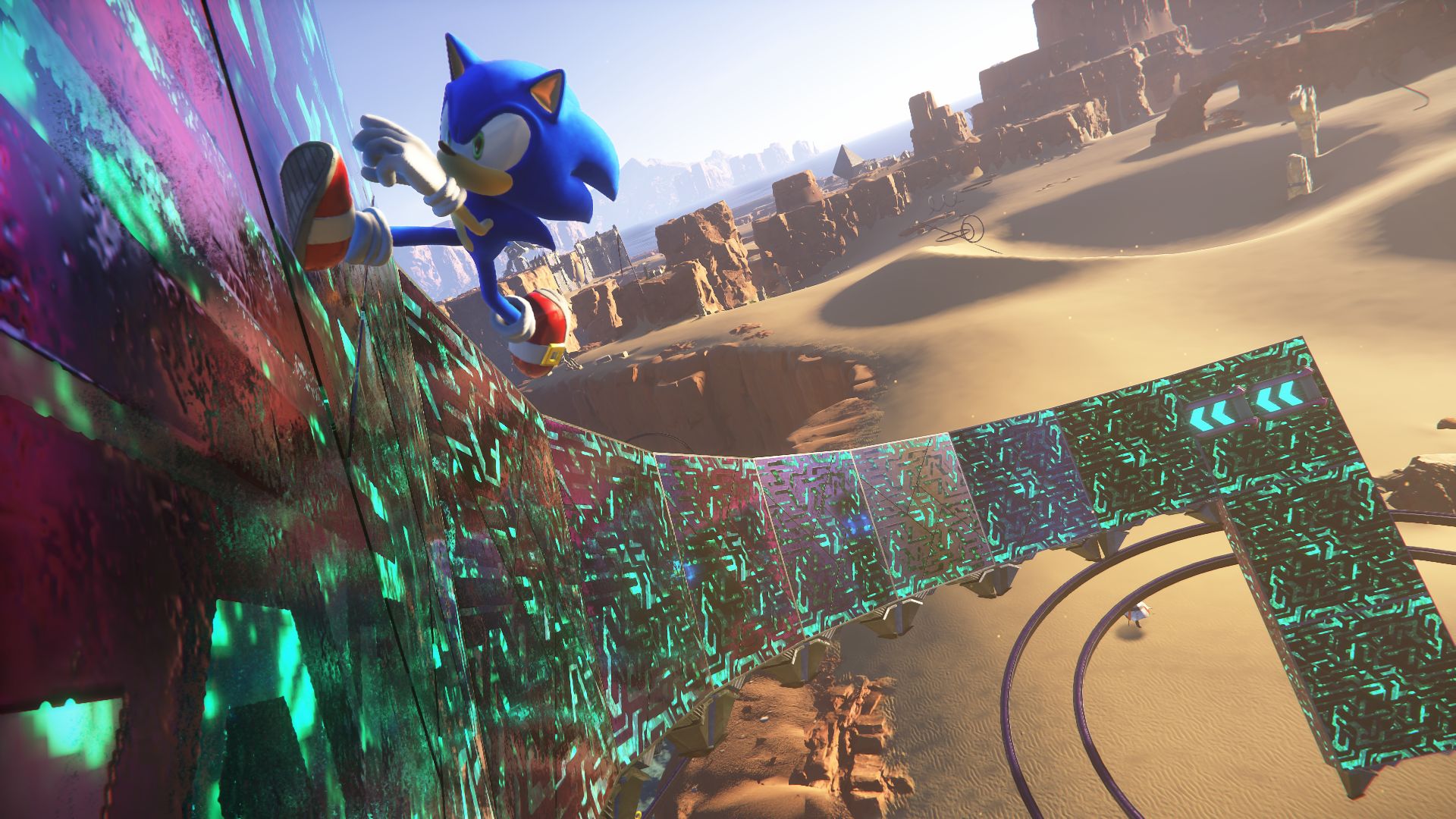

Pokémon is of course barely relevant here, but that means of going sort-of-open-world might sound familiar to those with a close eye on Sonic Frontiers. It’s another knot in the thread, which we can now rather neatly tie from Breath of the Wild’s leap into the fully open world to Sonic, this coming November, doing the same in its own way. People do like to cut that thread, mind - or go further and suggest it doesn’t really exist. A common point made is that, while these games like to market themselves in the same way, finishing a trailer with a series mascot channelling a bit of Caspar David Friedrich by looking out imperiously over a green and mountainous world of adventure, that doesn’t mean the games are the same, or that one was inspired in an any meaningful way by the other. These games all have fundamentally different systems and different goals, after all, and so Breath of the Wild isn’t an influential game; it just had really influential box art. Playing some Sonic Frontiers, though, and speaking to Sonic Team studio head Takashi Iizuka, you see where that kind of thinking goes wrong. The common thread here isn’t a mechanic or premise like Zelda’s discovery-via-systemic-physics, or Pokémon’s catch-and-catalogue scientific method. It’s the step back from that: a realisation that the medium as a whole has evolved, at least a little, and that there are some players who want to decide their own goals and discover things for themselves. Some kind of openness - an open world, or area, or with Sonic Frontiers what the team is calling Open Zone - is the natural next step. But it’s the goal of all these games that ties them together: to take that next step while still keeping the series’ essence intact. The “essence” of a great Sonic game, Iizuka says - or just how he’d define the best parts of playing it - is really the “fun feeling” you have while moving. “So whether it’s a 2D game or 3D game or an Open Zone game, it’s really that sense of enjoyment that I’m running with Sonic at a high speed and [thinking]: this is fun, and I’m having a great time. That to me is the essence. “It’s very clear to me that just going fast does not make it fun. You could be, you know, just running in a straight line superduper fast, but it’s going to be kind of boring, you’re not going to feel like you’re going fast. And it’s really through the design of the course, and the things that you’re having to do, where you feel that speed and where you feel that fun. So regardless, if it’s a 2D game, or 3D linear zone, it’s that sensation, that feeling when you play with Sonic, that the team is really focused on.” Iizuka explains the history of Sonic as really “20 years or so” of following the same “linear game design” style, with the 3D linear zones of Sonic Adventures, in 1998, the first “evolution” of that. But at this point, he says, “the team kind of felt like we were hitting a limit of what we could do, and how we would innovate on the game. And we really wanted to challenge ourselves to do something new and make something that is going to last for the next 10-plus years as a new game format. This is really that third or second - I guess this is the third - kind of iteration of Sonic the Hedgehog gameplay.” “It’s taking that same Sonic high speed action that we know from the linear and 2D platforming, and putting it in that open space. And that’s what the Open Zone concept is.” Circling back a little later in the conversation, Iizuka elaborates a little more on the perceptions of what “Open Zone” really means. “I think a lot of people, if they’re just kind of looking at the videos, or they see a screenshot, it’s very easy for them to see the open space and say it’s an open-world game.” But “open-world” is something he associates with “creating a whole world and creating other characters in that world, and putting you as a character alongside those other characters in the world and saying, ’now go do the things you’re going to do in this world that I’ve created.’” With Frontiers, he explains, “that’s not what we’re trying to do - that’s not the intention behind the game. The Open Zone concept really came from, ‘we want this open space to exist’. And inside of this open space, we want Sonic to be able to do high speed action platforming; running, jumping in like a playground for Sonic. We want that to be in an open space, not in a linear format. “The purpose of that open area is completely different for us versus like an open-world game,” he says, “where we have a town on, you know, this side of the map, and we want you to walk across to the other town because some character told you to go over there and get something for them.” The core challenge of this for Sonic Team - albeit a challenge that Iizuka describes as necessary - was making that leap to having you be able to run around freely in open areas, without losing that Sonic essence. “When we talked about the different games,” Iizuka says, “it’s really not the game telling you what to do next and providing you with your next challenge. It’s creating this open area and filling it with tonnes of things to do. Instead of the game telling you what to do, the user is now deciding what the user wants to do next. And that was really the challenge the team needed.” Some of that challenge can be felt in playing Sonic Frontiers. It’s an odd game, with Sonic’s traditional gameplay probably the furthest from a natural fit out of any of the series that have made a recent leap to open worlds. An Open Zone, if you’re still not totally sure, is essentially a giant level. A big plot of land that you can roam around freely, with some decidedly Sonic-y structures and bunches of enemies dotted across it for you to parkour around and about at speed, or, if you prefer, totally ignore as you explore. This time I played the second zone in Sonic Frontiers, called Ares, which is more of a desert-like biome with old, noticeably ring-themed ruins sprouting up from the dunes, and which featured slightly more elaborate obstacles than the first area shown to press earlier this year. Your core objective was also explained a little more explicitly. What you’re trying to do is get the Chaos Emeralds out of things called the emerald vaults. In order to do so, you need to first defeat bosses called the Guardians. All of the Guardians, when you defeat them, will drop a portal gear, those portal gears will unlock the portals, which take you to Cyberspace, the 2D-style linear areas you’ll have already heard about. In Cyberspace there are different challenges, and completing the challenges will get you a vault key, which you can use to unlock a vault and get a Chaos Emerald. And onto the next. This is a process that seems convoluted to the point of byzantine, but is actually a bit more simple in practice: you defeat a boss to unlock a more traditional Sonic course, to unlock the next zone. It’s like that with much of Sonic Frontiers, it seems. Dropping into the game’s second level you’re assaulted with icons and collectibles - collect some kind of ring/orb/gem/fragment/seed, you’re told, to help free Tails, or reach a new area, or, in the case of the deeply Breath of the Wild-like “starfall” events, which turn the odd night-time into a Blood Moon-style frenzy of resurrected enemies, you’ll need to sprint about collecting star fragments to spin the wheels of some kind of abstract fruit machine, which sits awkwardly across the middle of the screen. There are also things to collect which let you level up, unlocking new moves for combat or the ability to chain more elaborate combos together, and all of this comes back to your main job, which is to run about the world following whatever twinkling, pinball platform catches your eye. (These little courses are fun, and very reminiscent of Sonic Adventures, but also oddly passive, effectively asking you to tap the odd jump or dash button at the right time while you’re catapulted across the sky). That combat, meanwhile, is fine for the moment, although not sweeping me off my feet just yet - likely because the real enjoyment will come with chaining movement and attack combos with the type of fluidity I’ve neither mastered nor unlocked at this stage. My opening boss fight was really quite simple - do a quick, passive platforming course up to its eye-level to fight it, where you have to hop between three circular rails that surround it, avoiding attacks long enough to fully trace a path around the entirety of each hoop, and then spend a few seconds kicking it in the face. The main challenge isn’t mechanical so much as one of clarity: depth perception is an issue, especially once the final stage kicks in. It took a lot of squinting at an already-close screen to discover hazards were actually hopping between adjacent rails themselves, following me between them, and that I could simply tap jump to avoid them entirely. Depth is a similar issue for the Cyberspace zone I played, which was unlocked after defeating this boss and pinging around another course of air-pinball to a special obelisk. There’s been some chatter about these zones “reusing” old Sonic levels, which Iizuka is quite keen to clarify. Cyberspace zones are what he describes as “the digital expression of the worlds in the memories of Sonic the Hedgehog.” So when you go into the portal, he says, “it’s a world that’s created from Sonic’s memories, the places that he’s been to like Sanctuary, Green Hill, and so on - Cyberspace is creating a world based off of his memories. “We want to kind of reuse those memories - like the memories we have as well, because we played the games with Sonic - but the team is doing it intentionally, to kind of poke at those little points that some players are gonna pick up on immediately. Like, ‘I remember this exactly!’ And we are making levels that maybe look different, but feel the same as other things you have experienced. There’s going to be a mix of those very intentionally nostalgic or familiar areas, but there will also be some brand new things nobody’s ever seen before.” Familiar or not, these can be a bit of a struggle, with Sonic’s dash going remarkably far and rendering him impossible to manoeuvre in the air, to the point where it’s hard to travel at any kind of speed at all. That’s likely at least part of the goal here - high-speed travel is as much a reward in Sonic as it is the way to earn it - but it’s one that felt entirely beyond me in the 20-odd minutes I had with the game in total. It’s another reminder that Sonic Frontiers has been a challenge to make, albeit clearly a welcome one too. That combat, for instance, was described as a dilemma but an interesting one: “I wanted to have more things that Sonic can do, more attacks Sonic can have,” Iizuka says, “but when you start making Sonic kind of stop and attack enemies, you’re defeating the whole ‘high speed action, I need to race to the finish line’ kind of concept for the gameplay. And that’s kind of what the problem - the difficulty - was in putting in that combat system. If you put it in, you’re kind of stopping the gameplay, but if you don’t put it in, then the enemies just tend to become objects to get in your way that are stopping you from reaching your goal. “So it was really [a question of]: if we’re gonna put in combat, which we wanted to do, then how could we do it? The answer that we came up with is this Open Zone format, because you’re now free to do whatever you want, you’re on an island, looking for things to do.” In other words, he says, “engaging in combat is something that we want to provide, but if you’re going to provide enemies you’ve got to make sure it’s fun, and that’s really where you think, ‘Well now, we need to put in a combat system so we can have people want to engage the enemies, defeat the enemies, enjoy it, and then run off and do whatever they want to do next.’” It’s not unfair to say that some of that tension is still present in Sonic Frontiers, but the upside is that it makes for a decidedly curious game to play - something new, if nothing else. A game that’s taking the leap to an open format, like plenty of other long-running, previously linear series before it. But one that’s also doing it in very much its own way - just like its fellow mascots have done, too.