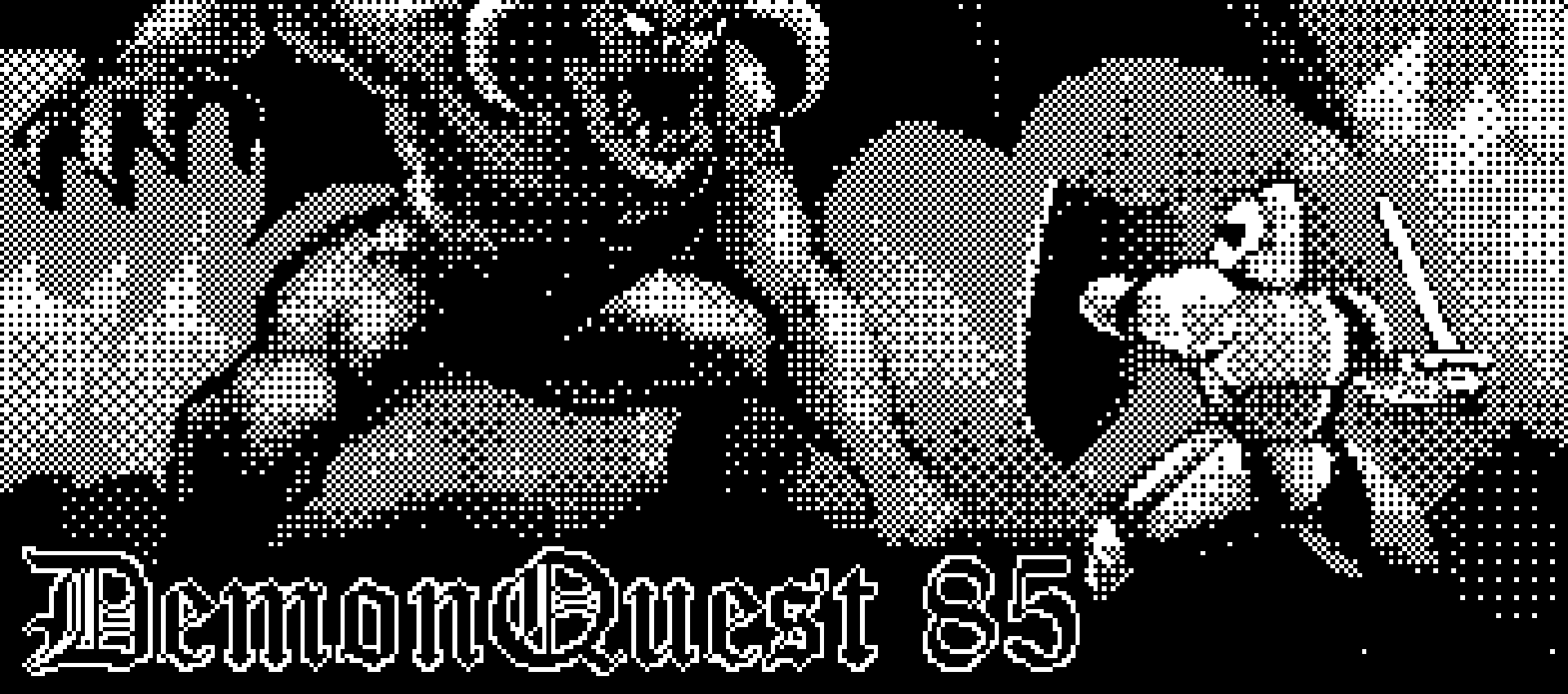

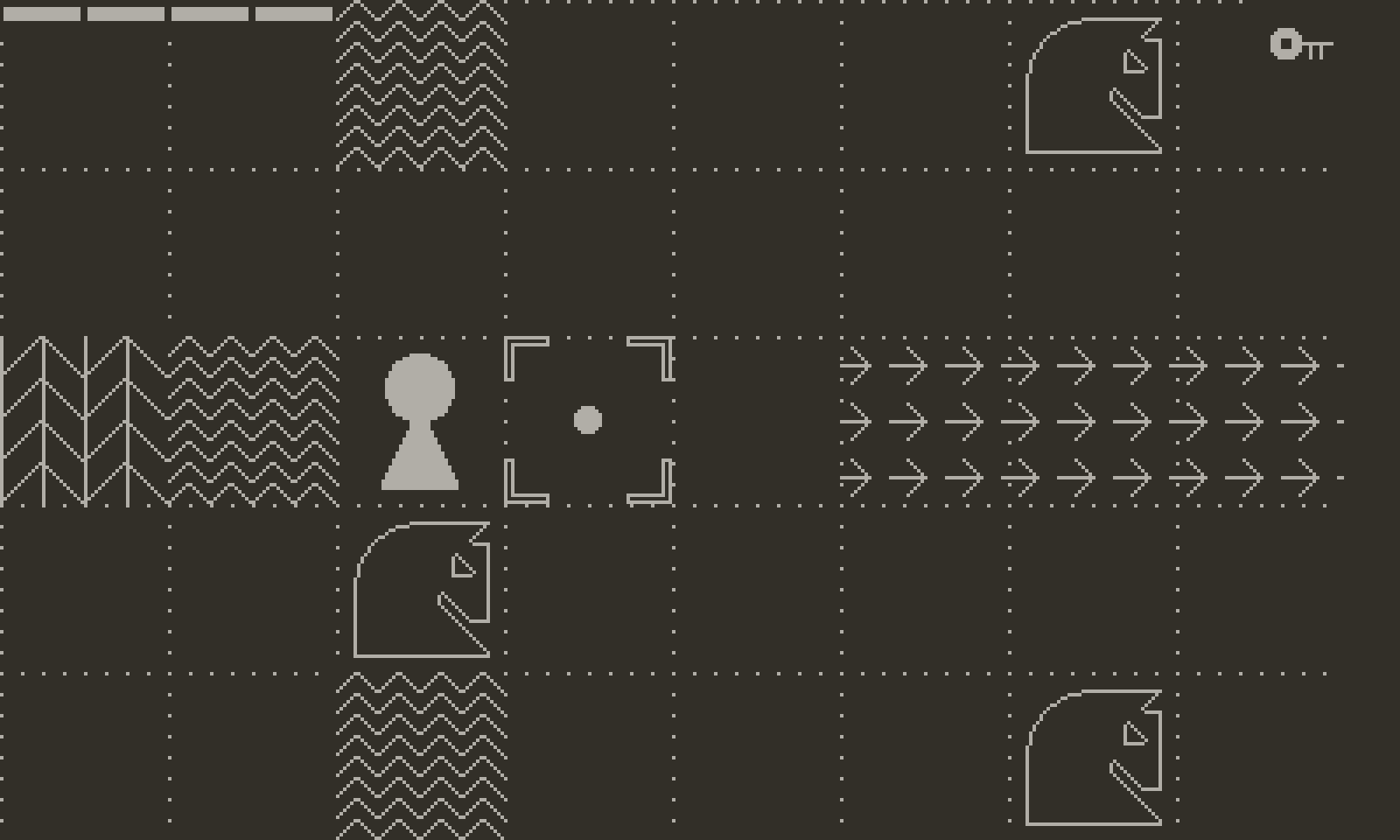

Freedom to roam! And there’s a peculiar freedom of form too. Handhelds are allowed to be odd, because they’re objects - clue in the name here I guess - to be held in the hands, and the hands are curious things themselves. Just look at them. Maybe this is why handhelds are where normally sober hardware designers deploy rear touchscreens, or two screens and a hinge and stylus, where a cartridge might come with its own little rumble pack, or a light sensor for weaponising the sun as you fight digital vampires. The Playdate, which I’ve spent the last fortnight with, features a crank! It features a crank. And yet. Long before Playdate and its crank arrived, some part of me already understood that every handheld is, before anything else, a puzzle to be solved. A lovely, playful, speculative puzzle. What is this funny new thing particularly good at? What makes it singular? Where does it really come alive? What, ultimately, is its intention? All this. Yet what I didn’t understand until Playdate is that solving this puzzle can take weeks - can be, in fact, something of a game in itself. Sometimes, design provides the perfect analogy. Playdate, on the surface at least, is a deeply nostalgic machine - an oddball handheld made by a team who genuinely understand this crucial thing: that all handhelds are at least a little oddball in the first place. And a part of that nostalgia is down to the screen, which is monochrome and unlit and instead requires reflected light in order to display anything. There is a serious lineage to this kind of screen. A Nintendo lineage. And so I prop myself by a window, the sun illuminates the cheerful little device in front of me and I remember, for the first time in years, propping myself by another window in a bedsit somewhere to illuminate Advance Wars on the Game Boy Advance. But that analogy I was getting to: Playdate is a far more complicated object than I initially thought it to be - a far more complicated proposition. There is nostalgia here: a handful of games dutifully offer spins on Zelda, on the scrolling platformer, on Breakout. These games are great, actually. But the more I play, the more that stuff feels like a path that leads away from what’s really interesting. There is a far more fascinating device in here - an experience that, at its best, can be almost alien in its weirdness, or that reaches back to…? I don’t get to see it all the time. Like that magical, nostalgic, reflective screen, I have to angle things just so. And then suddenly it reveals itself. Here is what I don’t think Playdate is. And I’m starting with this because it’s exactly what I initially assumed Playdate was going to be. Playdate is not WarioWare: the console. I think there is humility here in this regard. WarioWare made its own console from rules and shifting button contexts and a flicker book of art styles. It made new hardware from software, turning the GBA into something unprecedented, and then it did it again, with additional hardware this time, in the form of WarioWare Twisted. I’ve spoken to a number of people about Playdate over the last few weeks, and the initial confusion is always the same: where are the gimmicky games? The toast catchers? The chicken kickers? The three-second remix of Mario 1-1? Tell you what: they aren’t on Playdate, because Playdate isn’t that thing you might think it is. Be generous: you can see why I thought it might be, though. Playdate as a proposition is whimsy itself. A uniquely self-conscious console. Surely this is hardware from people who drink Custardos and ping around the Bay Area on unicycles with underlighting. The whole thing is tiny: a square about the size of three or four craft beermats stacked on top of each other. But it shouts! It’s yolk - not yellow: yolk - the national colour of extroverts, of gabbling runaway ideas pinging off in all directions late into the night. (Also, Pavlovians might note, the colour that McDonalds uses for the Big Mac font.) There’s an A and B button and that reflective screen - all very Game Boy - and there’s a lock button at the top. Press it twice and the machine wakes up, one cartoon eye at a time. There’s a menu/home button tucked rather awkwardly next to the screen, offsetting it slightly. (If not for this button, incidentally, and the speaker below it, the whole thing would remind me very powerfully of the 3rd gen iPod Nano, that squat little bruiser, which was also perhaps the most personable bit of technology Apple has turned out since the original Macintosh.) Oh yes, and to the side: the crank. It rests with its handle tucked snugly into the machine, to fix it in place, the way that swans, say, tuck their heads under their wings when sleeping. Pull it out - not talking about the swan anymore - and you get a little digital fanfare. The arm of the crank is cool metal. It’s nice to turn it, even when you’re not turning it for any reason. Something of the early twentieth century to it, the era when cranks really had a proper place in the world. When they were getting your jouncy Model Ts and Citroens purring. When they were bringing you the latest newsreels from the REO wagons with their mounted cameras. The Playdate’s main menu uses the crank, so you scroll up and down through its games by twisting it. You might trick yourself into thinking there was actual clockwork in there: secret gears and escapements and whatnot, only the crank itself protruding. The in-game pause menu uses the crank too, though you can also use the d-pad. And the games themselves? We will get to this. To Crank or Not to Crank is one of the big unspoken design questions with the current wave of Playdate games. Playdate has buttons and a lovely retro screen - really lovely, I was able to use it in the evening, and by bedside light in the middle of the night - and that crank. It has an accelerometer too, which I discovered entirely by surprise in the middle of a game about making potions. The sound is surprisingly loud and suits the 8- and 16-bit games that Playdate offers very well: lots of chugging and pinging, but strings can be audibly plucked too. That’s the device. So what about the games? Caveat here: a big one. Playdate is an open system and encourages people to make and share their own games, using an SDK and sideloading. This, I suspect, is where the machine will live long term. Homebrew but with no need for jailbreaking. A sort of idealised PSP (with a crank). This is an article in itself, but it is one that cannot be written yet. (I can at least tell you sideloading is a doddle - drag-and-drop through your account on the website, and then find the new game ready to download in Settings.) So what about the games you’ll be playing now? One of the things about Playdate I was most looking forward to was not the games but the delivery system. This is a weird thing to say, but in keeping with a device made by the Custardo and Unicycle set that I perhaps unfairly have in mind, I guess: the flourishes matter here. Playdate games come in seasons - the first season, which I have spent the last two weeks with, is 24 different titles. Buy Playdate and you get the whole season. But it arrives two games at a time once a week, accompanied by a purple light on the device to tell you everything’s ready for you. I love that. In principle I love that. Living in a sort of suspended period of Christmas - not for nothing do the games appear in the menu covered in digital wrapping paper - and waiting each week for New Game Day and its purple light, the same way I wait each month for Edge Thursday. Switching analogies, it’s a tasting menu, I guess, albeit a protracted one. In truth, when I actually had a Playdate in the house, this delivery system initially seemed to be one of the least successful aspects of the console for me - or perhaps it’s more accurate to say it’s the most double-edged; I did grow to see its appeal. Playing through the review period, the whole thing was sped up - two new games each day. Yet still. It’s definitely fun when the light blinks telling you you have new stuff, but I discovered that the chances that I was just then in the specific mood for the games actually delivered were not high. For a few days I sat in a kind of mounting boredom as games I didn’t fancy playing at the moment piled up, as the anticipation proved extremely sweet but the delivery was gritty and naff. It was odd. If you’re like me, you approach each new videogame as a chance to fall in love. This disposition was tested by my first few days with Playdate. Instead, Playdate started to work for me only when I had a sort of critical mass of games installed: eight titles which I had tinkered with and rejected upon arrival, but which I could now scroll through and pick between in an idle moment - what might suit me today? It was like paging through a magazine, looking for something to read. Helpful analogy, that. Ultimately, I think this unusual model for game delivery works - and I really think it does work - for the same reasons it remains clear that in some ways magazines are more interesting technology than websites. This is because, bundled up with the stuff you wanted to get, you get a bunch of other stuff you didn’t realise that you might actually adore. You have no choice but to burst your own bubble. I hate and would never buy an arcade space game. (Not me talking, I am straw-manning here for a second.) Too bad. Now you’ve got one. Give it a go. Maybe it’s great. Let us speak of Season One, then. 24 games, a lot of them good. I’m not going to talk about all of them as I don’t want to spoil too much. As I’ve said before, there is something dutiful in the delivery at times - there’s a Zelda-type thing, a few arcade things, something a bit like Pokemon. But there’s real diversity too: diverse creators from diverse backgrounds, and diverse ideas. It took me a while to get over the WarioWare thing. So at first I gravitated to games that seemed short and spiky, with obvious hooks, often leaning heavily on the crank. Again, I’m going to try to avoid too many spoilers here, because I want you to enjoy Season One for yourself, but I can tell you that there’s a game that uses the crank to move someone through time and space and past obstacles, but its gimmick never came alive for me. There’s a puzzle game in which you crank your way through a series of circular chambers, but it still seems like an exercise in craft: good taste and not much else. The arcade games are often great - one game sees you using the crank to control an elevator as you move penguins between the floors of a building and is a panicky delight; another sees you cranking sinuous arcs and ribbons through space to capture glittering stars, every bit as lovely as it sounds. But for every game that incorporates the crank elegantly, another will crowbar it in, merely using it as a way of moving story sections along. To crank or not to crank? The answer, of course, is that you should follow the grain of the design. Panic, which makes Playdate, has itself provided two games for Season One, and it’s telling that one is all crank, all the time - Breakout set inside a circle, basically. The other, and I’ll start naming games here, because they’re games I want you to definitely check out, is Inventory Hero. Inventory Hero does not use the crank at all as far as I can tell. It’s a fast-paced RPG in which you simply manage the inventory of your character as they battle enemies and level up. Choose the best pants and the best sword! Swap stuff out before it breaks! Stop the rabbits from filling up all your inventory slots. It’s a great game whatever you might play it on. On Playdate it feels like something more: Permission to forget the crank? Permission granted. It’s through other games that I started to truly understand what Playdate is, however, and through them that I learned to start loving it a bit. I am going to be brisk here: DemonQuest 85 is like nothing else I have ever played. It’s a narrative puzzler in which you page through a book on demonology looking for some monster or other to summon, and then making sure you have the right criteria - right audience, right music, the right offering. It’s absolutely stellar. I suppose you could argue it’s an inverse Obra Dinn, but it doesn’t feel like that. It feels like a battered Point Horror with the best bits marked in dog ears, and I love the fact that it’s only on Playdate - that it’s a weird, gloriously trashy game trapped inside this weird machine. The monochrome screen display comes together with the heavily-lined art to create something that feels like grimy book illustrations printed on dirty paper. The ambience! That same ambience permeates a game called Sasquatchers, which is basically Advance Wars but with people who want to photograph cryptids rather than deploy tanks and soldiers. Played out on a grid, regularly interrupted by moments in which you chat with your crew and turn the crank to line up pictures, it’s a playful, handicraft thing. I love it and I want to play more. On it goes. Zipper is a luminously brisk samurai game from Bennett Foddy, which looks like it could be printed in the puzzles section of a newspaper each dat. Spellcorked! is a work-out for Playdate’s headline inputs as you crank potion ingredients in a pestle and mortar and then tilt to decant them. Echoic Memory is a music-matcher which, of course, has a bizarre narrative threaded through it. Pick Pack Pup is a match-three game and satire of fulfillment center work. All this is great, but then there’s Questy Chess. Questy Chess, like DemonQuest 85, feels like one of those moments where you get the screen angled just right and you see what Playdate can be - maybe what it really means to be. Questy Chess is a chess-based action-adventure-puzzle game. A turn-based thing, with hints of Chip’s Challenge, which takes place inside a haunted operating system as you travel across houndstooth worlds, changing from pawn to knight to who knows what else, braving mysteries and a sense of dread and bursts of dot-matrix printing sound effects. It’s stark and inventive and thrillingly good, and it’s by Dadako, which means it sent me down the rabbit hole as I then discovered this team’s other games. All as it should be! It’s a clever puzzler, but it’s also filled with intrigue and a deep, sonorous strangeness, and no small part of this is down to the Playdate, where it lives, where it is trapped, as it were. The screen with its blacks and whites and cross-hatch patterns looks like nothing else I have ever seen in a game. It feels kicked free of genre and traditions, living on this odd little device, even as it draws upon one of the most famous games ever invented. At its best, Playdate feels like this: it feels like you’re getting these unprecedented things that live in an unprecedented place. Forget gimmicks and one-shots, Playdate comes alive, against all expectations, with the longer, more involved games, that encourage you to spend real time with the console and come back to it often. Take it seriously - in the best, most playful way, of course. Engage with it. It feels like you’re being beamed the video game canon from some other planet, two volumes at a time. And it’s wonderful. That’s not all it feels like. I am just going to come out and say this, because it’s odd and maybe it doesn’t make perfect sense, but it’s also true, and once I realised it I couldn’t shake it. Playdate doesn’t really remind me of a games console at all, even though it’s actually quite a good one. What it reminds me of is those trade paperback collections of Mad Magazine articles you used to see stacked up in junk shops - glossy covers battered, paper stained a weak lightbulb yellow, ink mimeo-thick and gritty. Its best games look, on that screen, like they have been thickly, loosely, enthusiastically printed in someone’s attic. And I flip through them like I used to flip through Mad: what’s the idea here, what’s going on, what style is used, what traditions are being subverted? Playdate loves demons and space and private eyes and heaven and all the kinds of stuff Mad loved. It’s in love with the rich and trashy pleasures of yesteryear, and of reworking these pleasures in unusual ways. Again and again with Playdate I come back not to technology, but to print. Mags. Old paperbacks. Things I could already waste hours of my life cheerfully plucking through, ink on the thumbs. This is probably why I’m only now thinking of the things I should be telling you about the tech, but which I can’t. Partly because I’m not qualified - I’m not DF - but partly because it simply doesn’t feel relevant. A few days back someone asked me how much storage Playdate had, and the question completely confused me. Dumb as this sounds, it does not feel like a machine with storage (although I gather it has 4GB). It feels like a haunted beermat on which games occasionally appear. What’s the battery like? 14 days standby and eight hours active, apparently - I have charged it a few times and it doesn’t feel egregious. Does it have a headphone jack? Yes. Can I make it output on a computer? Yes, using Mirror, which also lets you use a pad. But really, treating Playdate like technology will always feel odd to me. Maybe there’s one way it all makes sense, though. Attached to my memories of Mad magazine are inevitably a bunch of memories of early home computers - the C64 and Amstrad in my case - and there’s a lot of that DNA here too. Games straight from someone’s attic workspace or the desk in the bedroom. Games straight from their weird head and their weird perspective and their weird take on what games should be. At its best Playdate gives you this - along with the nicely handled Zeldas and the Breakouts and the things it seems to feel it should give you to be well-rounded. Now I’ve seen it, I want more of it.