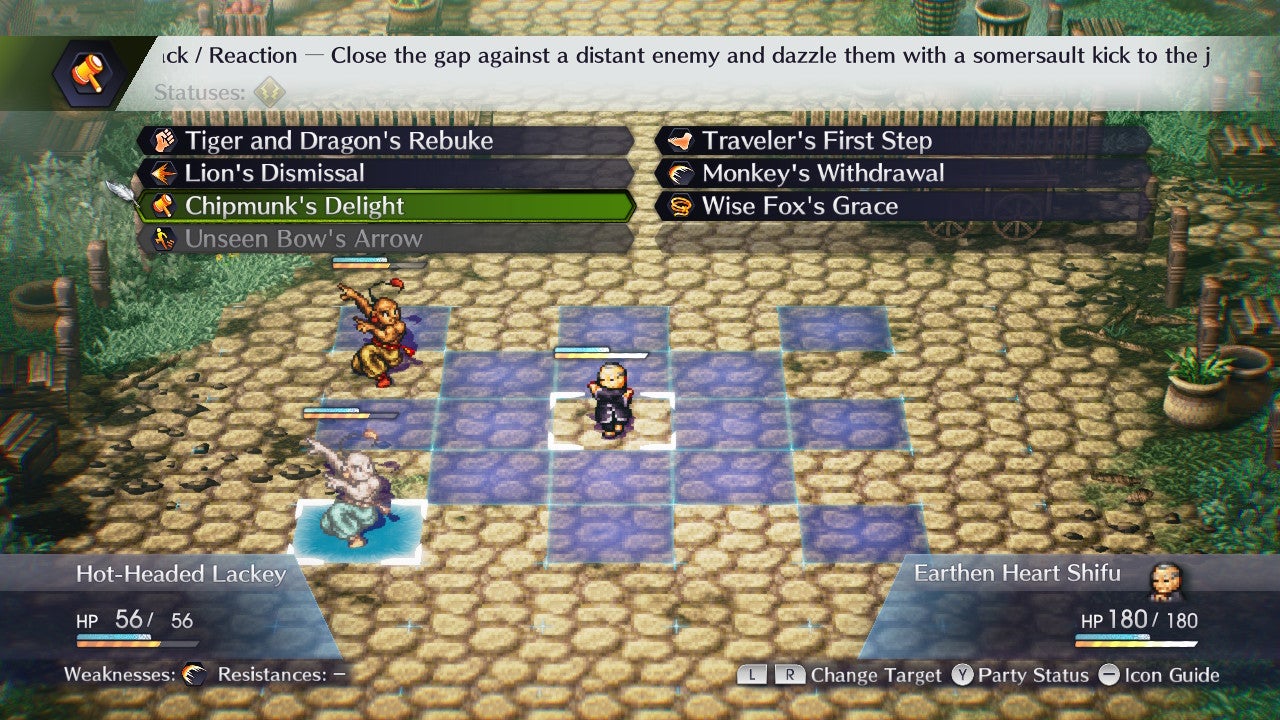

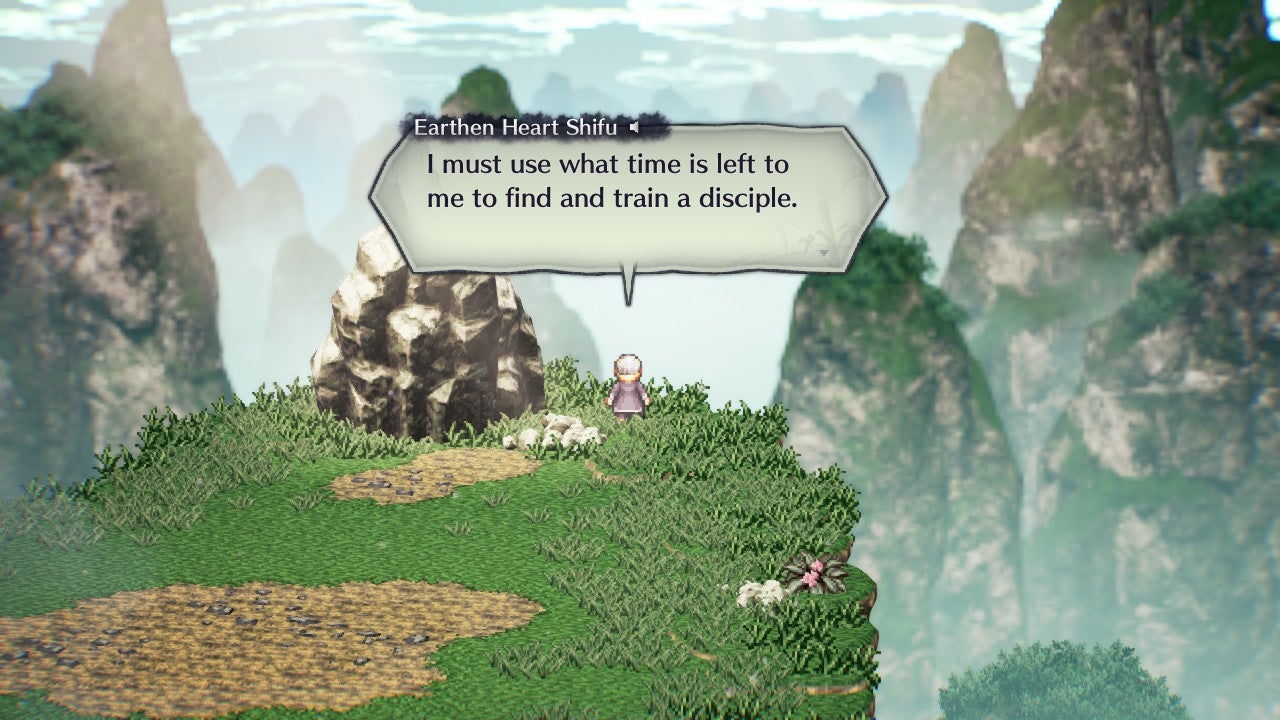

First released in 1994 and remastered using the same, sprites-meets-polygons visual style as Octopath Traveller, Live A Live is essentially Sidequest: The Game - as I probably should have realised before I compared it to a level-select cheat in Sonic. It’s a collection of loosely interwoven, 1-3 hour tales set in different historical and/or fantasy periods, each its own colourful interpretation of what an old-school Squaresoft role-playing game can be. Much as with sidequests in traditional single-narrative RPGs, some chapters are more successful than others, but all are engrossing experiments, and while it’s slightly thwarted by the stop-start anthology structure, the overarching, grid-based battle system is worth the 20 hours or so it’ll take you to reach the closing credits. The game’s nine chapters (seven available to begin with) share levelling and equipment systems, but each is otherwise a distinct yarn with a separate protagonist - typically a bloke, it must be said, with women featuring largely as damsels in distress - and party members, a signature mechanic or two and a flavourful writing style. On the one hand, you’ve got distant prehistory, in which a shaggy Flintstoner and his simian pal stumble on a runaway girl while hurling poop at mammoths. This chapter is a bawdy comedy written in grunts, gestures and speech bubble emojis. On the other hand, you’ve got a Wild Western chapter starring a Man With No Name - well, a Man With A Customisable Name - who teams up with his nemesis to defend a frontier town against outlaws. This episode is feature-film length with a chewy, saloon-bar script, built around a single set piece puzzle: arm the townsfolk with traps to bump off as many desperadoes as possible before the final battle. The cheeky advantage of Live A Live’s anthology format is that the components don’t have to be universally excellent. The intrigue of the game is half sheer novelty value and half watching a development team strive to make the same pieces fit a different narrative setup. I wasn’t that keen on the imperial China chapter, for instance, in which an elderly martial arts master puts three disciples through training battles ahead of a showdown with a local hoodlum. You’re invited to play favourites, but there just isn’t enough time for those mentor-pupil relationships to flower. Likewise, I wasn’t that sold on the far-future level, where you play a sentient robot on a starship transporting an alien monster. The only combat, here, takes place inside another videogame in the vessel’s rec room; you’ll spend the bulk of the time trundling between elevators in pursuit of a torrid star-faring soap opera, give or take a few bouts of hide-and-seek. But I found myself cheering the developers on regardless, because after all, who doesn’t want to see the creators of Dragon Quest try their hands at Alien or a kung fu epic? In any case, you can always bob between chapters using a single save file if you’re losing interest, and the challenge is balanced such that you can tackle them in any order. Some chapters feel more like jokes. The present-day (aka early 90s) section is a stripped-down spoof of Street Fighter starring that one party member in many turn-based RPGs who only learns abilities by copying enemies. Playing as a would-be global champion, you pick opponents from a coin-op arcade menu, then dodge around to tempt out their juiciest moves before KOing them. It’s pleasantly silly, though not nearly as daft as the near-future section, which, deep breath, stars an orphan delinquent with telepathic powers, who teams up with a punk biker, a Doc Brown-esque scientist and a turtle-driven robot to stop a technology company turning souls into fuel. It starts you off selling takoyaki in the park and stealing clothes, and ends with a mech punching the gizzards out of a massive bird. There are several toilet-based puzzles plus a jaunty urban overworld, and you get abilities that cause targets to confuse you with their own mothers. I enjoyed this chapter partly because I had no idea what would happen next. But by far my favourite was the Edo period Japan section, the quiet genius of which is that it pits you against the game’s own levelling system. You play a shinobi invading a fortress to rescue a prisoner and murder a lord who dabbles in the dark arts. You’re told to keep the body count low, and you’ll miss out on certain rewards if you build up a killing streak, but if you run past or flee every encounter you’ll get wiped out in battles that can’t be skipped. Fortunately, you can murder non-humans such as ghosts with impunity. This proves the basis for an extended social stealth puzzle, like a Hitman mission set in Sekiro’s Ashina Castle, in which you track down enemies you’re permitted to slay, while feeling out the behaviours of a clockwork playspace full of swivel doors, secret chambers accessed using your ears and some nicely creepy moments involving puppets and shadows. Where the present-day and far-future chapters are one-shot affairs, the Edo section demands to be replayed, and is the part of Live A Live I’d most like to see developed into a standalone game. The major drawback of Live A Live’s anthology structure is that the combat doesn’t quite evolve over the course of the first 15 hours, because each of the initially unlocked time periods needs to be accessible enough to serve as the player’s first choice, with its own miniature arc of challenge and complexity. Fortunately, the two concluding chapters turn up the heat, and the final episode especially is an opportunity to really put the battle system through its paces - recruiting previous protagonists from around the map and venturing into character-themed puzzle dungeons to obtain their ultimate weapons. So, combat! I should probably get round to telling you how that works, shouldn’t I? The bread-and-butter: characters have action bars that fill up when another character moves or acts. Battle unfolds on cramped square grids, with some beautifully drawn bosses taking up a third of the playspace, and you can move around freely during a character’s turn until interrupted by an enemy action. Attacks and abilities affect different patterns of tiles: melee moves, of course, target adjacent tiles, while fancier spells might strike out diagonally. Some abilities affect the terrain, filling squares with water or fire. Others have a casting time, during which enemies may slide out of the way or perform attacks that knock your character out of position. There’s a slightly excessive assortment of status effects, from poison and paralysis to debuffs that lock off certain abilities. Enemies may also be resistant or vulnerable to certain attack types, though this isn’t nearly as impactful as staggering foes in Octopath Traveller. While equipment choices can be decisive, you don’t have to do much pootling around in menus between scraps: characters heal completely between battles, while level-up stat boosts and unlocks are chosen for you. There are a few areas featuring random battles, but the majority of enemies are visible on the world map and can be easily outrun (the shinobi can also disguise himself as backdrop, letting guards wander through him). The battle system is weakest when treated as a no-frills, your-stats-versus-mine affair, and strongest when treated as an eccentric cousin of chess. It’s all about how those AOE abilities determine your understanding of the board, and by extension, of the characters in hand. The near-future delinquent is a glorified Rook, for instance, launching psychic blasts horizontally and vertically, which makes him less effective against foes that move like Bishops. The shinobi gets a few powerful AOE moves that leave terrain effects behind, but these also cover the tile beneath him, so you’ll have to keep dancing him around. The kung fu master lacks ranged attacks: he’s all about closing the distance, then using skills that move himself or his targets back a square - very much the wushu legend denying his adversary an opening. The cowboy, by contrast, is all about range and single-tile attacks: the point of thinning out the raider posse during the Wild West section is partly that he’s less capable in a crowd. The game’s most satisfying battles expand these underlying questions into full-blown spatial puzzles: these include scraps in which there’s an enemy leader, who can be slain to defeat all the rest. You’ll want to open the path to these VIPs by shattering formations with knockback skills and piercing shots, rather than systematically purging the rank-and-file. Live A Live is a chronically whimsical game, with far more fart jokes than sonorous philosophical takeaways. But there’s an affecting, gently radical morale beneath it all about making connections between people in very different times and places. Without giving too much away, the final reveal is that each chapter is in some ways the same struggle, with evil appearing less as a final antagonist than a toxic meme outside of linear chronology, which has to be defeated again and again. In that regard, Live A Live is both the perfect project for and one of the original wellsprings of Square Enix’s current, wistful approach to retro RPG development, which is less about simply restoring old games than splitting reality off into a meta-historical dimension, where SNES-brand pixel sprites coexist with sparkling 3D lighting effects and cinematic transitions. As I wrote of Octopath Traveller, these games aren’t just homages with a few modern features, but alternate retro-futures that feel at once quaint and slick. They blend what was and what is into what might have been, which cultivates a speculative, open-ended view of gaming history that disagrees usefully with the exhausting industry rhetoric of hardware generations and soon-to-be blunted “cutting edge” technology. It is, you might conclude, a vision of history that is all sidequest.