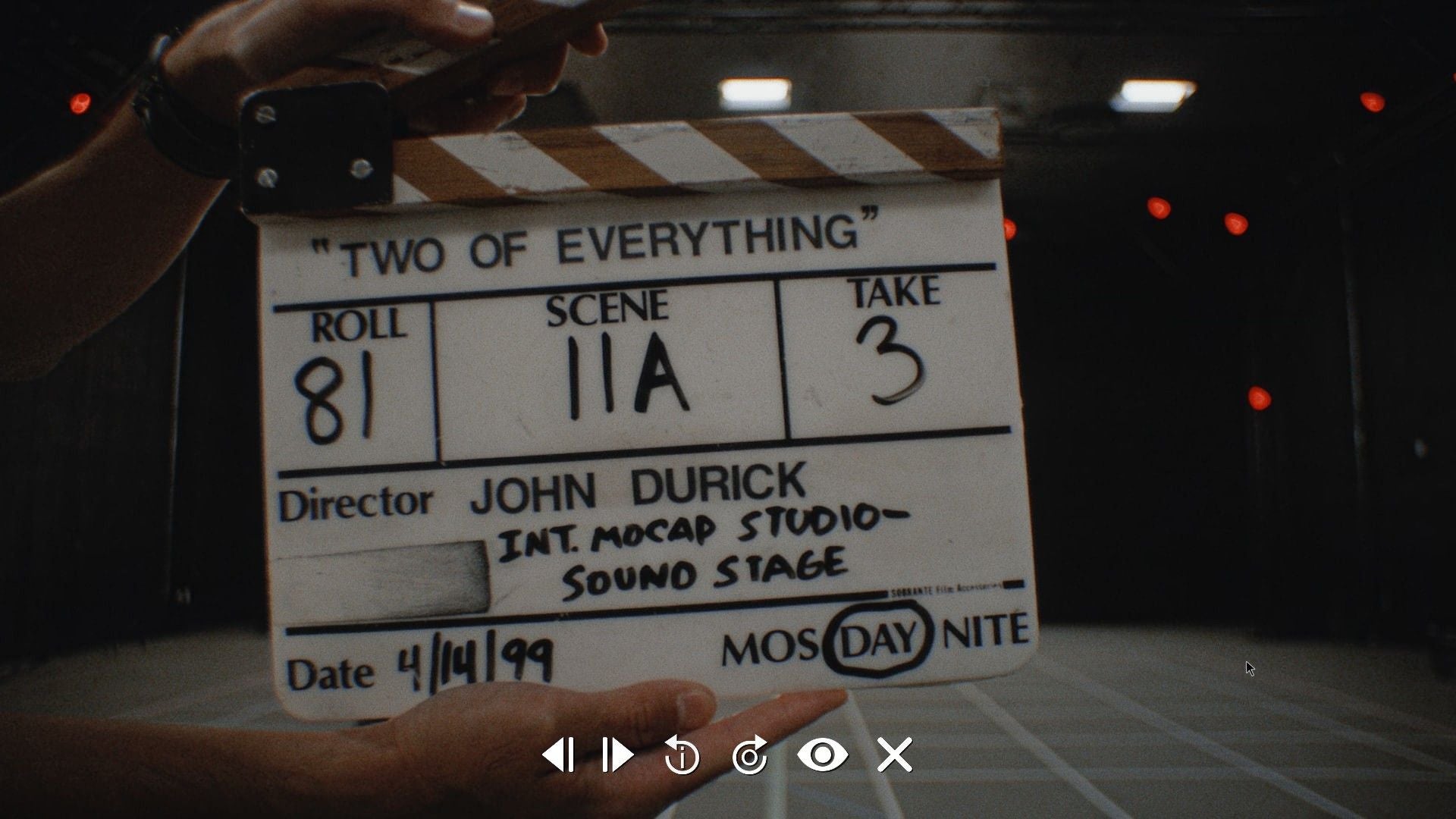

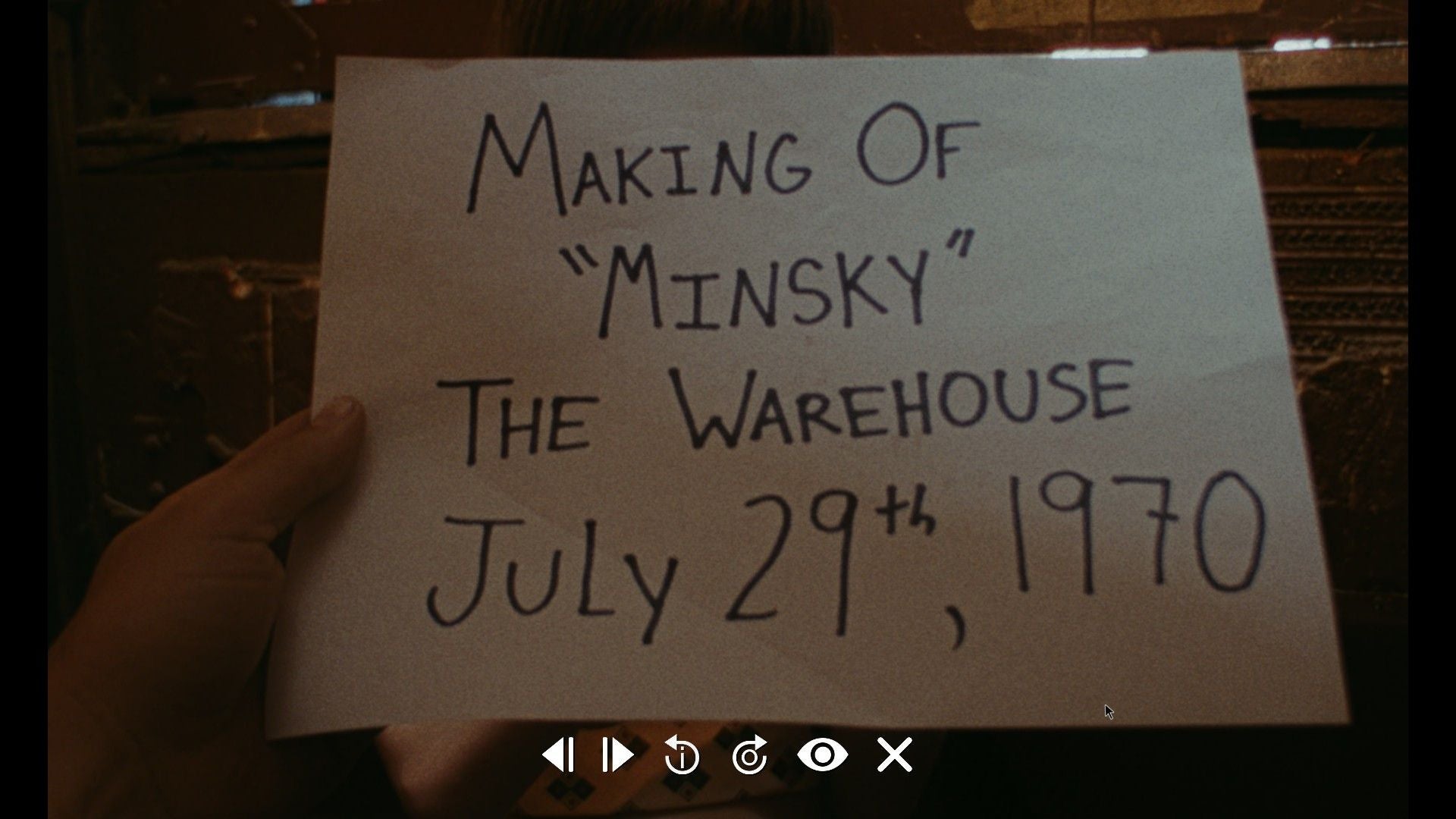

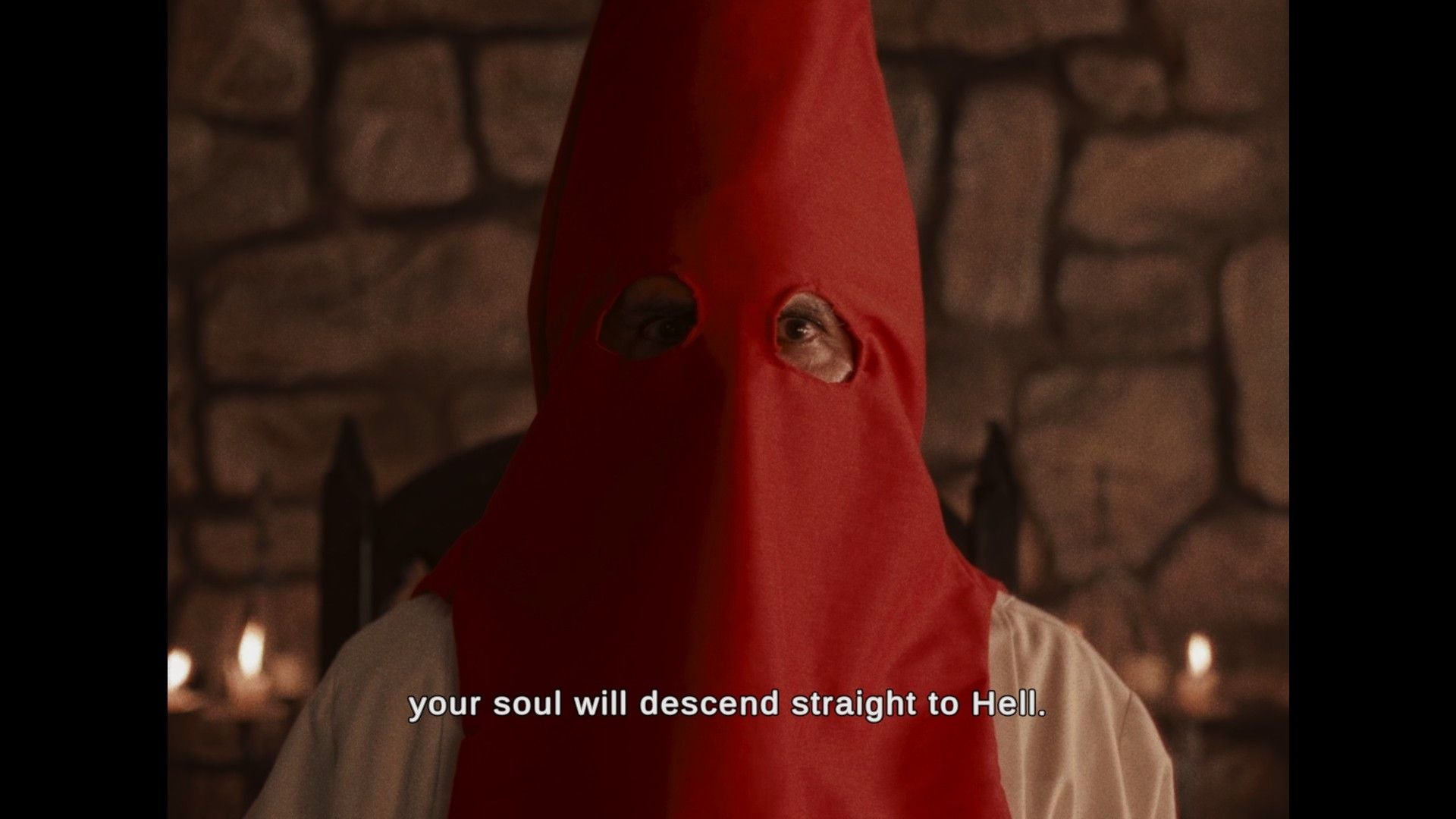

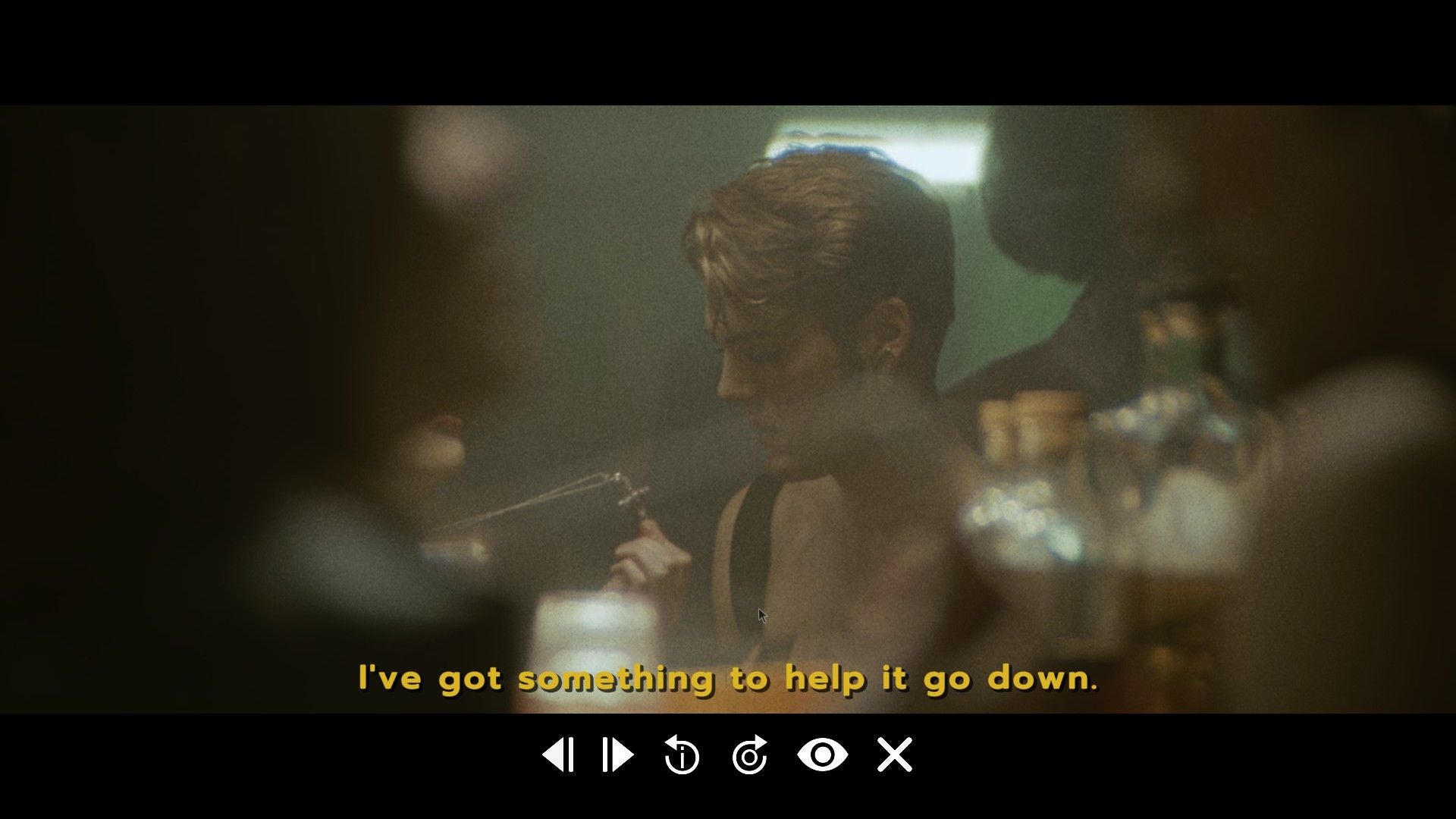

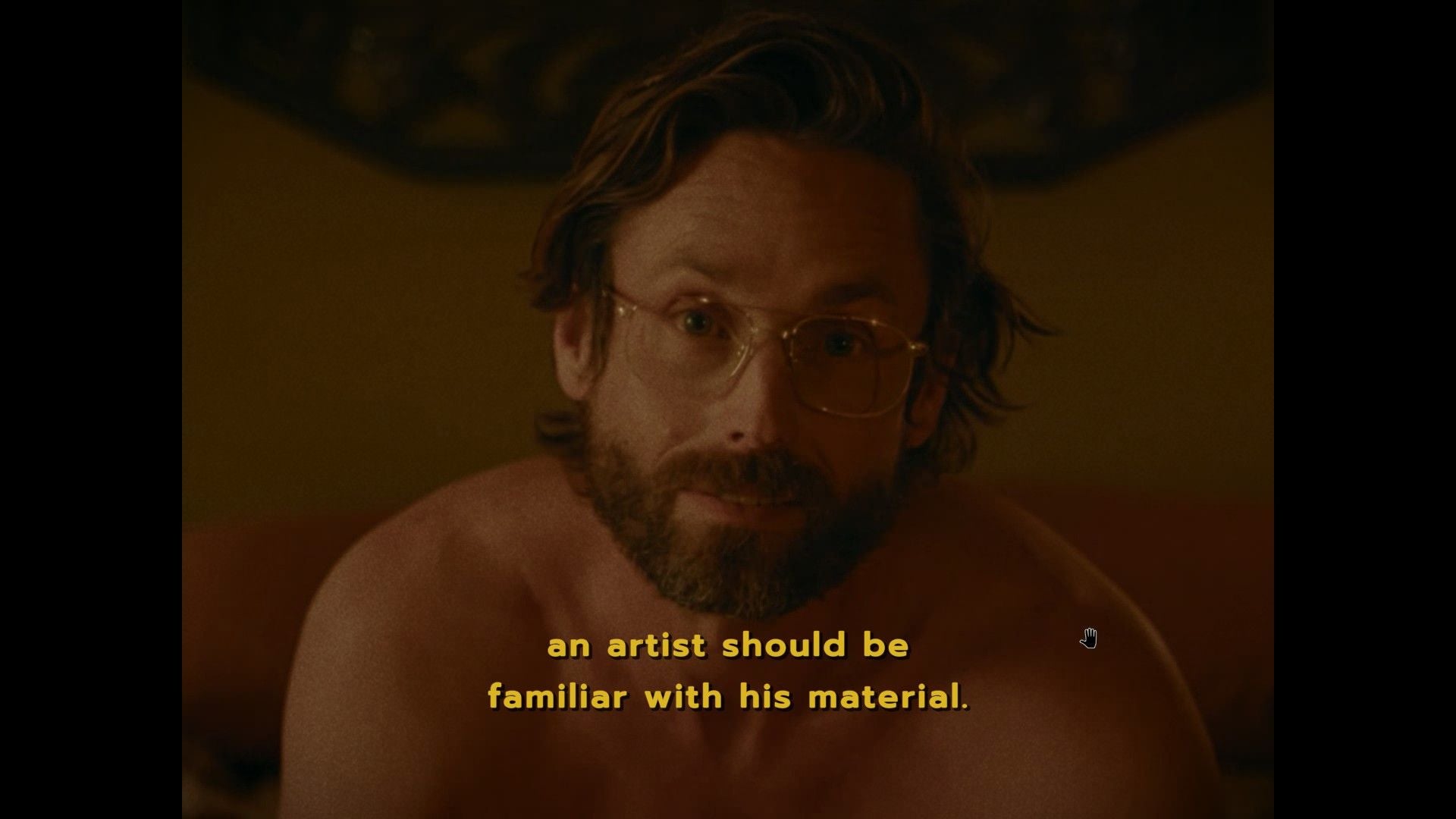

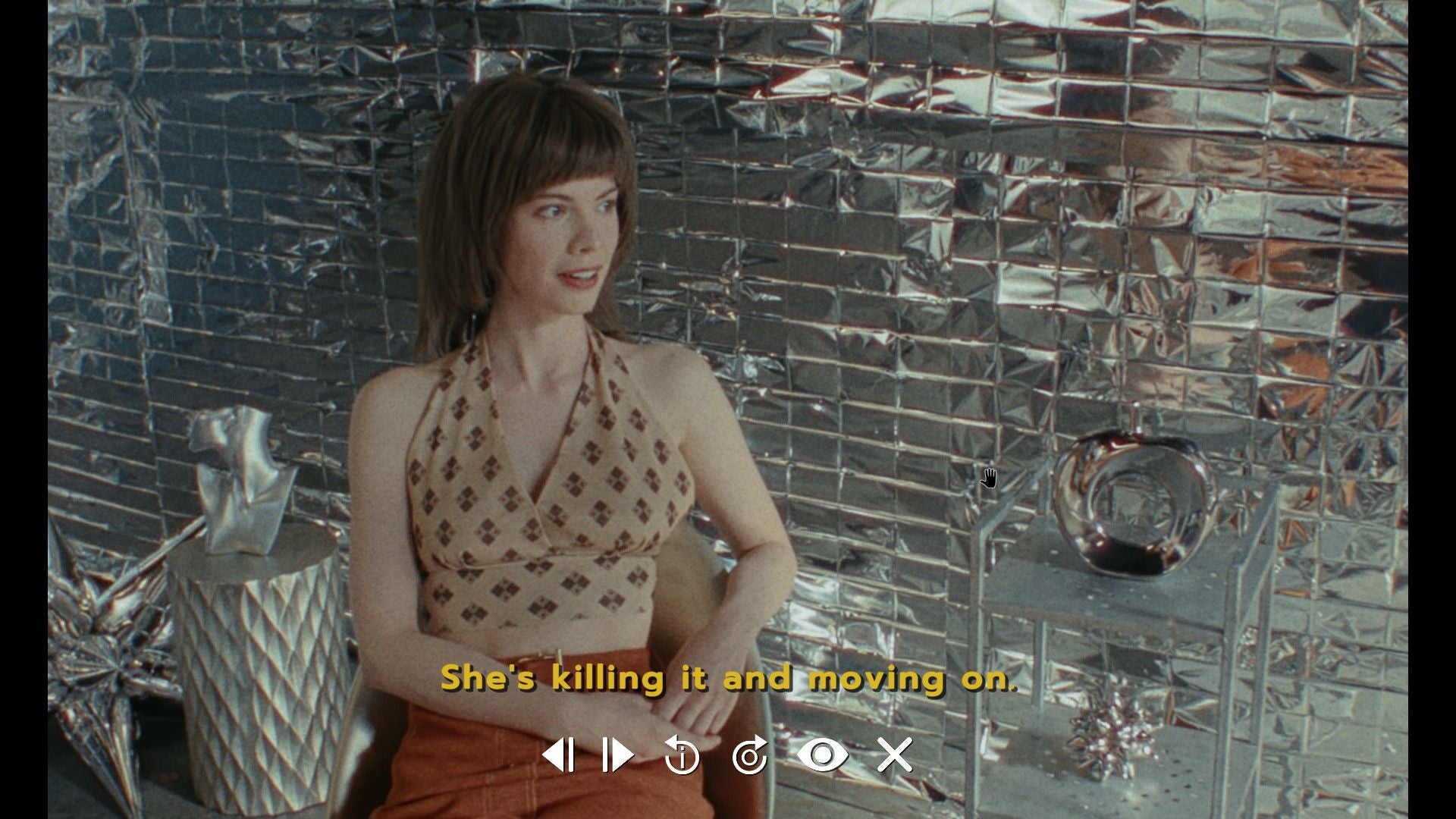

But the reason he’s haunted by Kubrick, as opposed to possessed, is that while Nolan’s work has always channelled a bit of Kubrick’s, it’s never truly become it - never quite ascending to that plane. Nolan, since the still extraordinary Memento, has been a director who takes the themes, the scale, the technical marvel of directors like Kubrick and channelled these into making films that are repeatedly, often incomparably impressive. The problem, and the reason why it often feels like he’s carrying around this Kubrickian curse, is there is a difference between films that are impressive and films that are profound. The temptation for me here is to look at Immortality, a game of demons, vice, and backwards talking, centred on mystery and murder, and say that just as Nolan is haunted by Kubrick, Sam Barlow, Immortality’s director and co-writer, is haunted by David Lynch. That would be wrong, though, for one because Barlow’s previous games, fellow video-scrubbing mysteries Her Story and Telling Lies, have barely a whiff of Lynch about them. They are their own things. More than that, the influence here probably has at least a little to do with the involvement of Barry Gifford as Immortality’s fourth co-writer, along with Barlow, Amelia Gray and Allan Scott. Gifford is the author of Wild at Heart and screenwriter of Lost Highway, two films David Lynch directed. So no. Immortality and Lynch is really less of a haunting, more of a close encounter. The real parallel here is between the type of filmmaker Nolan is, and the type of game-maker Barlow is, and the types of things they make as a result. Just like Nolan, with Immortality Barlow has built a technical marvel that is impressive to behold. It’s the type of game built on layers upon layers of planning, of the kind you see with Nolan’s “plot map” drawn up for Inception. These structures are feats of engineering, stories that require blueprints, protractors, diagrams. What I keep coming back to with Immortality, though, is the job of an architect. Someone to ask how you build a structure but also what you’re building it for - to ask how humans not only tend to use a building to work or to live, but how they ought to as well - to take the engineering and put it in service to a bit of philosophy. Paste that slightly clunky metaphor onto making a video game, not least a game like this - a structure that should find it impossible to stand up straight - and you have an almighty task. It’s the one thing, above all else in Immortality, that you can feel Barlow wrestling with throughout. Let’s walk it back a bit though. Immortality is, like Her Story and Telling Lies before it, a game about trawling through reams of video footage to solve a mystery. The mystery in this case is that of Marissa Marcel, an actress who stars in two films in the late 1960s at about 20 years old, then disappears, then reappears in 1999 to star in another film. She also looks the exact same in 1999 as she does in 1968, but nobody seems to mention this. (This includes in the ‘About’ blurb, which is tucked away on the main menu but something I would call essential for players - it should arguably be part of an opening crawl, something all players see on screen when they begin rather than a missable bit of detail, but that’s a quibble.) The footage you have is from these three films, plus some clippings from rehearsals, behind the scenes documentaries, and the very occasional personal film. Your task is to piece together what happened, scrubbing back and forth in different clips at different speeds - but crucially, navigating through them via Immortality’s major invention, something it calls the concordance feature. This is effectively a hyperlink, something you click on to travel from one on-screen element to a different clip with a matching one (Immortality, being meta, calls these match cuts). You might click on a key, in one scene from the 1968 film Ambrosia, for instance, and arrive mid-way through a scene featuring another key in Two of Everything, shot in 1999. Immortality’s bravest gambit is to tell you this is possible, then simply drop you into a scene and leave you to it. The result is messy, maze-like and unclear, but by dint of that far more organic than a linear mystery that drags you through it by the nose. There are multiple hyperlinks per scene - usually about three to five on screen at once, give or take - and so the possibilities spiral outwards dramatically. From that first scene you will, I guarantee, end up in an entirely different place than I did, arriving there by an entirely different route. Quickly you will feel lost, and soon after that you might feel, if you’re like me, as though you’re doing something closer to workplace paperwork than playing a game. The first analogy I had for Immortality was my own inbox, an exhausting, incomprehensible spaghetti-mound of information to sift through, while looking for an attachment or an invoice, my own system of labelling and filing flattering to deceive. Get beyond that, though, and Immortality will morph from a depressing Tuesday afternoon at your desk into something far more salacious and exciting, a wicked web of overtly-themed, cinema-history vice. Apples, snakes; oranges, nudity; keys, mystery; guns and knives and bloody hands. Probably a Maltese Falcon if you look hard enough, somewhere on a shelf. Characters will wink at you down the lens - Immortality loves breaking the fourth wall, loves to lampshade, to allude to, to reference a reference; it is beyond obsessed with cinema and this is barely the start of it - as they move from one societal taboo to another. Themes recur and recur until they seem like much more than just a theme - more a pointed remark. On-screen nudity in a work of gothic erotica (a scene where a character performs sex in a way that is taboo, in a film about the taboos of sex, in a game about…) Or an actor (playing an actor) taking pretend drugs only to find them real. Or a murder, a case of double identity, on and on and on until your brain turns to soup and your list of “favourited” clips, ones you’d linked together for some long forgotten reason, loses all meaning and sense. To let you toil like this is inspired, a cruelness balanced perfectly by Immortality’s brevity - you’re never lost for more than a couple of hours - and executed with confounding, magnetic, vicious brilliance by Manon Gage, who plays the many versions of Marissa Marcel. Barlow has a thing for Hollywood doppelgangers, an issue that can rear its head with independent, film-adjacent media like this - and one that can lend plenty of similar games a sense of student short-film earnestness, and awkwardness. Gage is the spit of Anya Taylor-Joy, which had me worried, but she is wonderfully cast here, slipping effortlessly between Marcel’s many roles like costumes in her wardrobe. The rest of Immortality’s cast do similarly well, across sets of varied grimness, from sordid erotica to 70s seed to modern pop-trash (characters love to call things modern - is Barlow playing with analysis, are the themes deliberate comments on that? Are they red herrings? What’s the bet there is a red herring in the background somewhere?). Each of these settings becomes alarmingly gripping, each a point of genuine fascination on its own, thanks in large part to their wonderfully poised performances, intentionally split across hamminess and self-regard. It’s easy to forget these are often actors playing actors, repeatedly chopping in and out of character, while also firing hints at you, the player, down the lens to think about what you’re seeing, or follow a link elsewhere. I can’t fathom how they pulled it off. Those hyperlinks could be people or they could be objects - often they are props, and scenes will usually feature at least one that seems to have been focused on with a kind of directorial eye (so obviously, in some cases, that you assume this must be Barlow being meta again: look how I prominently place this vase in the frame, how I light this book, mention that apple, in the same scene where a man plays a director based very obviously on Hitchcock, in black and white suit and tie). Occasionally, their obviousness feels less deliberate and more a necessity, a means of getting you to click the “right” concordance: a runner handing an actor a gun, but holding it with such modelled poise you’d think you’d slipped onto the shopping channel. But that question - am I doing this right?! - pervades throughout, and the uncertainty became, at least for me, part of the fun. My suspicion with Immortality is that there is a right way, and that I did not get it right. At one point I unlocked an achievement for “what happened to Marissa Marcel”. A little later I reached the end credits. I could not tell you what happened to her, why it happened, what it means, what Immortality really wanted from me all along. I’ve wrestled with it and compared notes, doubted methods, gone through favourites and more. I barely touched the various means of organising and filtering the footage - should I have? I was too busy leaping from one sub-mystery to the next, too hooked - surely the right thing - to pull back out to the overview and note down where I was. Surely the wrong thing, given the ability to do so is there, and so emphasised at first before sending you off. But I found the things - I’ll talk around their exact nature, don’t worry - that I believe I’d been put there to find, and those achievements did pop and the credits did roll. This is a blessing and a curse for Immortality. Barlow has succeeded, in a way, in cutting me free and letting me find a thread of my own through his remarkably networked world. But upon reaching the other side I’m not entirely sure he wanted to. I think I’ve been freer than I was meant to be. I think I still have too many dangling threads. And this is why, when I think about Immortality, I can’t escape the plight of poor Christopher Nolan, who once asked why so many audiences tried to “solve” his films, instead of simply letting the films wash over them. I’m loath to explain filmmaking to anyone, let alone him, but I do think I know the answer, and it’s the same dilemma that stops me really falling for Immortality. People try to solve his films because he doesn’t really make films. He makes puzzles. Immortality, I feel, is a puzzle. An immaculately conceived puzzle, built with superlative skill - and genuinely thrilling in its own right. But it’s hard for a puzzle to feel profound.