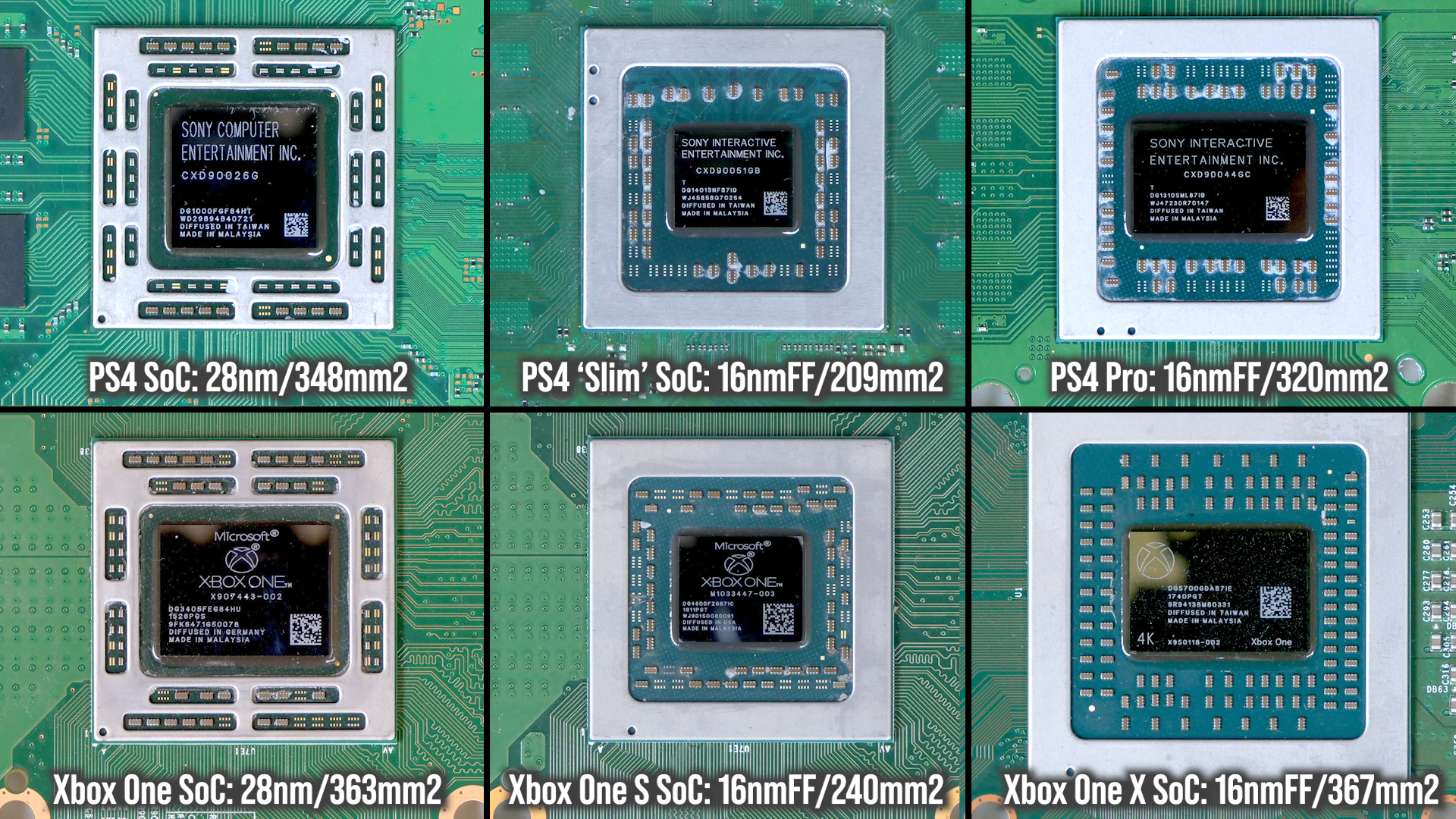

There are a number of reasons to bet against the arrival of enhanced consoles - not least because we’re still mired in an interminably long cross-gen transition that looks likely to extend into the third year of this generation. PS4 Pro and Xbox One X were also designed to support a new breed of ultra HD display and there’s no evidence to suggest that 8K or even 4K at 120Hz stands much of a chance of justifying more powerful hardware. Perhaps more importantly though, there’s the question of economics, the idea that Sony and Microsoft may not find the route to an affordable console in current conditions, while the rampant inflation, a cost of living crysis and the spectre of recession means less money in the pocket of the audience. Then there’s Xbox Series S. The reason why it exists is extraordinary, told in depth to Digital Foundry by Xbox’s chief architect, Andrew Goossen, back in 2020. Put simply, the reason why Microsoft launched two consoles rather than one is that the idea of Xbox Series X reducing in cost over time no longer looks viable. Faced with that startling reality, Microsoft made the call to launch a cheaper, less capable machine from day one. In effect, we got the mid-gen ‘Slim’ refresh alongside the top-tier model simultaneously because the cost reductions over time aren’t happening. In fact, in the current climate, inflation makes the consoles more expensive to make. Meanwhile, chip manufacturer TSMC is hiking prices on silicon wafers and demanding premiums from some of their biggest clients. It’s a far cry from the cost reductions we’ve seen in the past. “Series S has been very impactful for us. As we design our new consoles for the new generation, we’re very much looking forward through the generation to be thinking ahead - like, how does this work? - and that’s why we got to two consoles at the same time,” Andrew Goossen told us in our Series S big interview. “We are facing a big change in how consoles are designed. I believe when we first started building the original Xbox 360 - the smallest one without the HDD - that cost us about $460. By the end of the generation it cost us around $120 - and that cost reduction path was driven principally by silicon cost reduction.” Progress in chip manufacturing technology is progressing - 6nm, 5nm and even 3nm nodes are looking good. This means that similar to the 28nm to 16nm shift we saw in the last generation, chip designers can still integrate more transistors into smaller chips - exactly what made PS4 Slim, Xbox One S, PS4 Pro and Xbox One X viable. Improved performance and better power characteristics are available, meaning that we’re still set to see progression in PC CPUs and GPUs. However, there’s a problem: shrinking a chip no longer comes hand-in-hand with a cheaper chip. “What [the new process are] not bringing any more is a good cost reduction, cost per transistor - and so this has foundational impacts to console development, because now we’ll get cost reductions, but they’re slowing down and it won’t be nearly the magnitudes that we’ve seen before,” Goossen explained. “And so that was another one of the reasons why we felt that we really had to do Series S at the beginning because we had to design for the future. For the first time, we had to have the entry-level console at the beginning. Previous generations were kind of easy because at the beginning of the generation, you make something really expensive - put as much silicon and as much performance as you could into it - then you would just ride the cost reduction curves down to mass market prices. That’s not there anymore.” The image above shows the situation as it was in the last generation. With PS4 and Xbox One launching in 2013 at 28nm, we saw a pair of fairly large processors. With the move to 16nm FinFET in 2016, the reduction in cost-per-transistor opened the door to two scenarios - the smaller, cheaper ‘Slim’ console and the enhanced ‘Pro’ model. You’ll note that generally speaking, the 16nm enhanced processors were of similar size to the 28nm originals. The reduction in cost-per-transistor made a $399 PlayStation 4 Pro possible. Microsoft’s more ambitious console with its outsized chip and 12GB of memory necessitated a price bump to $499 a year later, but the same principle applied. Now, what if cost-per-transistor remains static? The only way to launch an enhanced console would be to raise the price still further in a world where Series X and PlayStation 5 are already more expensive than prior generations. In short, the same reasons why Microsoft built Xbox Series S makes the concept of launching an enhanced model far, far more challenging. If the platform holder couldn’t see a way to make a cheaper Series X in the mid-generation, it stands to reason that an even more powerful console with twice the transistor count couldn’t be possible at $499. Beyond that price, the concept of a console as a mainstream product doesn’t begin to make sense. So, Andrew Goossen’s comments are, of course, two years old now - so was he incorrect in his assessment of cost-per-transistor? The key is to take a look at equivalent markets where competition is intense - and there’s no better example than PC graphics. Even factoring out the mining boom, manufacturers’ recommended retail prices are only moving in one direction. A Radeon RX 5700 XT launched at $399, its 6700 XT replacement at $479, the following 6750XT refresh at $549. Goossen talked about improved power and performance characteristics and we have indeed seen faster clock speeds and higher power draws - good for selling PC components but not especially compatible with a fixed console design. You may have also noticed that neither AMD nor Nvidia are able to aggressively undercut the other in terms of price-points, usually the sign of a healthy competitive markets - and exactly what happened when AMD disrupted the CPU space. General parity in prices comes about generally because they’re both limited by the cost constraints imposed by chip manufacturers and memory suppliers. There’s perhaps an even bigger question to address with regards the concept of a Pro or enhanced console: is the mainstream gamer actually as wedded to the concepts of more power and higher performance? The reality is that Microsoft’s gamble on Series S has paid off. Reliable data suggests that, by and large, the junior Xbox has sold as well as Xbox Series X. We’ve got some issues with some of the cutbacks Microsoft made to the unit - principally memory and memory bandwidth, not to mention the lack of disc drive - but the console itself is irresistible. Meanwhile, Nintendo Switch is on course to out-sell the already phenomenally successful PlayStation 4, despite launching over three years later. On top of that is the fact that the current generation of consoles are still rich in untapped potential - UE5’s The Matrix Awakens shows what’s possible, but we’ve yet to see a shipping game appear so far with the same level of ambition. CPU, GPU and even storage have barely been explored. That’s the case against enhanced consoles - but I do expect there to be refreshed versions of the existing hardware. There’ve been reports that PS5 will get a 6nm version of its processor, shrunk from the current 7nm, and Microsoft will have the same option. While cost reductions may be challenging, a smaller and more refined console will be possible and the expensive cooling solutions employed by both manufacturers can be pared back. Series X and PS5 hitting the $299/£250 sweet spot may seem unlikely, but there may be some movement on price. So, is there any chance at all of a $499 enhanced console, even if the appetite is there to make one? AMD’s Zen 3 and Zen 4 CPUs look like a considerable improvement over the consoles’ Zen 2. Meanwhile, if AMD can somehow pull off an architecture as good as RDNA 2, well, perhaps a boost to graphics may be possible - though remember the GPU multiplier between Xbox One X and Xbox Series X barely hit 2x, despite the Scorpio machine actually being mostly based on the original 2011 Southern Islands architecture. Improved clock speeds are definitely viable - there’s talk of RDNA 3 hitting 3GHz (PS5 holds the console clock record at a max 2.23GHz) - but that presents another major power consumption and cooling challenge. We don’t know about improvements to ray tracing performance which may be interesting but area of most potential interest concerns machine learning. Why double the size of your GPU when AI upscaling along the lines of Intel’s XeSS and Nvidia’s DLSS can deliver excellent 4K image quality at a quarter of the internal resolution? Integrating machine learning silicon opens the door to a smaller chip capable of much higher levels of graphics performance - an alternative to spending a lot more money on a much larger GPU. Machine learning is the new frontier in technology and some might say that it represents the biggest potential enhancement to the consoles we have today, a massive enabler for a new console generation further on down the line. However, there is an alternative vision - the idea that the console generation as we know it is dead, a scenario born out by the longest cross-gen transition period we’ve ever seen. There’s the possibility that the enhanced consoles as a concept may merge into what would traditionally become next-gen - console generations giving way to ongoing, ever-present cross-gen scenario, a more staggered version of the mobile phone upgrade cycle. The last couple of years of console gaming have shown that it might work and with game development getting ever more expensive, the idea of titles straddling the generations may actually make this scenario inevitable. What I can say is that development of console hardware continues at all of the major platform holders - but the concept of what a new generation represents may well evolve in step with the constraints they’re facing. How Sony and Microsoft will respond to the challenge remains to be seen but in the meantime, all eyes are on AMD. The need for backwards compatibility suggests that Ryzen CPU cores and Radeon graphics will continue to be at the heart of any new console hardware - and AMD’s innovations in the PC space will at least give us some idea of the fundamental building blocks Sony and Microsoft will have to work with in the years to come.