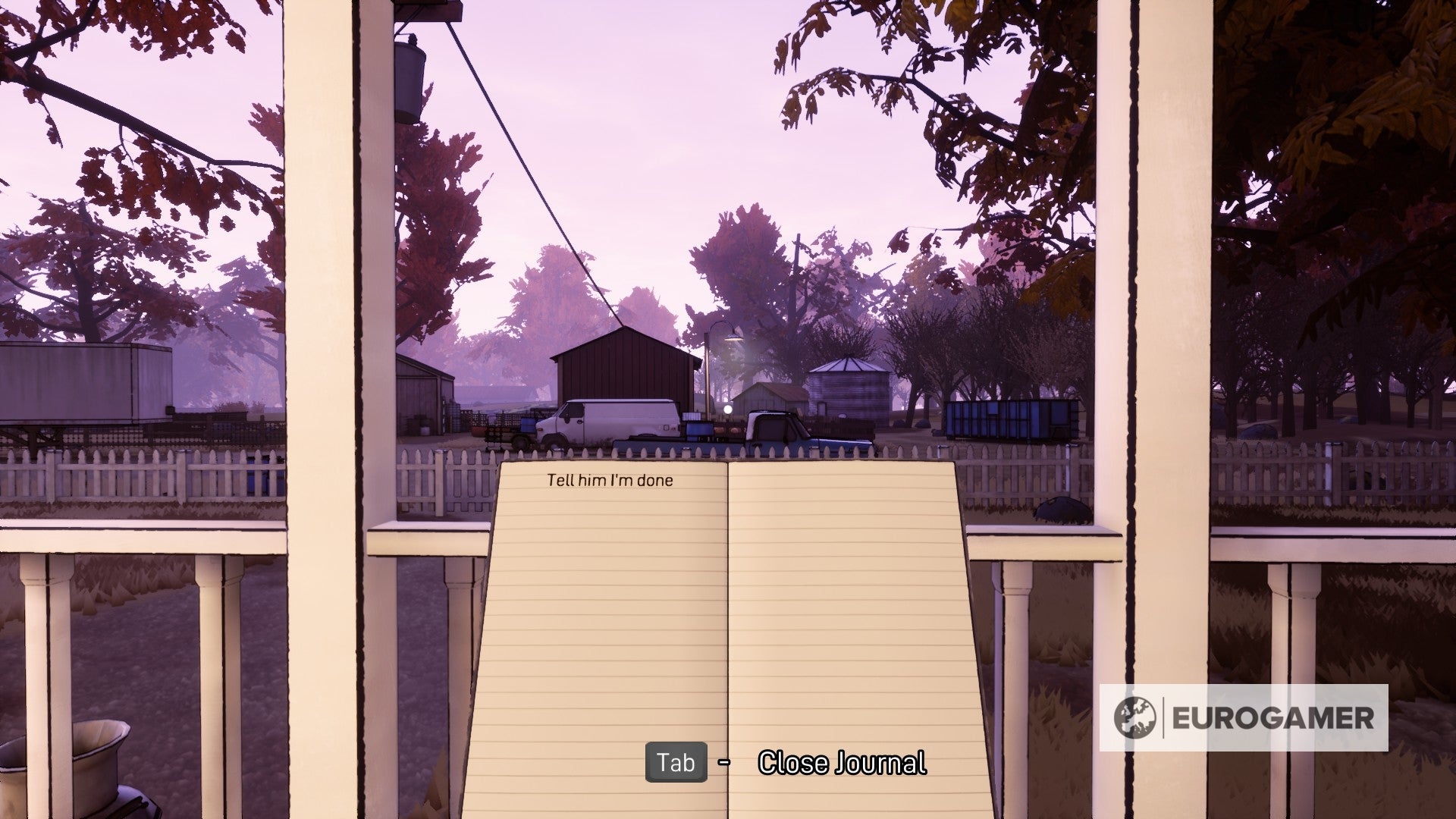

Maybe the best explanation is by example, which in this case is Adios. Adios is not a long game, and being of limited scope and budget it’s not particularly grand, either. You’ll probably finish it in one sitting, clocking in at less than two hours, and what you’ll do in those two hours is simple: you walk, and talk, and just live a day in another life. This is the magic of it though. Adios is just a story. There are little activities along the way - throwing horseshoes, catching fish, shooting clay pigeons - but little more, and they’re of little consequence, success or failure of little relevance to why those activities are really there. There are no puzzles or action, or even mysteries to untangle, and so the joy of it has to come from elsewhere: from the rare source of relinquished control - agency that’s sacrificed, as opposed to worshipped, allowing you to simply suspend belief and float. In Adios’ case this comes down to a pretty extraordinary strength of faith. We have plenty of games that are just stories, of course, and Adios’ story itself isn’t world-beating or earth-shattering or anything else you can describe with global scale. It’s small, and familiar, and quiet - but it has faith in itself, and that faith means it can back off a little bit. Its ending is fixed, and obvious from the elevator pitch (A pig farmer decides he no longer wants to dispose of bodies for the mob. What follows is a discussion between him and his would-be killer) and that means freedom to choose the dialogue that you feel flows, to role-play passively and naturally. The absence of mystery and action and thing-that-needs-solving, too, means it relies on you to self-propel, as a player, to find your own drive to proceed without being dragged, and that means you feel a little happier to stop. So? Where you stop then begins to matter, all of a sudden. When a game lets you self-propel like this, you’re free to wonder: what am I doing, why am I doing it, why was this scene put here, why does it play out like that? This, I think, is what I’m getting at when I’m very clumsily throwing around the word “texture”. If a story is a person going from A to B and the plot is the path they take to get there, the texture is the feel of the path, the tone of it, the shape of it, the specific placing of the twists and turns. It’s the how and why of a moment in a story: a pig farmer tells the mob he’s done. How? Well first he writes a list - the first thing you see in the game - and puts “tell him I’m done” at the top of it, and you’re now free to think about why. (Because he’s anxious about it? Because he’s certain he wants to, but is afraid he can’t, and writing a list might force him to stick to his plan? Because it’s also a very clever way to couple a “this is how you open your journal” tutorial with a foundational bit of exposition?) The temptation for many, I think, is to jump into all that and tell you what to think of it, to dig up the subtext and paint it across the surface. Adios, being just story top to bottom, instead grants you the freedom to look at it. It is not the most “textured” game ever, of course, because it has some technical limits and some constraints to what it can really do. But in its smallness it is focused, and so the texture that’s there - the time you have to sit by the lake and fish, to feed a final apple to your horse, to listen to the wind - feels richer and more pronounced, more available for you to see. Texture is what allows you to read something off a story, as a person who experiences it. Where Adios excels is how, rather than dragging you through its story, it gives you the peace and quiet to read it.